On a Saturday afternoon in February, 2021, the fourth in a series of transmissions beamed out via Vimeo and YouTube from an Austin studio called the Beatbox. It shows a Black man placing an Afro pick on an MPC sampler as if blessing—or tuning, or adorning—the room. Projections of deep space drift across the walls and turn the suit he’s wearing into a screen. Two mics direct attention to a low platform. As the man, tap dancer and choreographer Michael J. Love, begins to move, the stage becomes a dance floor, a canvas, a drum, and a time machine. A woman’s voice announces the start of “our inaugural ascent into the cosmos.” Love performs the motions of a body warming up, his form shifting as it relaxes into power.

The moment summons decades of Afro-futurism—from the transportive voyage of Parliament-Funkadelic’s Mothership to the cosmic groove of Detroit electro legends Drexciya, whose work imagined underwater galaxies populated by the descendants of pregnant enslaved women thrown overboard from Middle Passage ships—a movement that imagines alternate realities where sci-fi and the African diaspora intersect. Love’s body is present, but its motions evoke somewhere else. As the room fills with the warm thump of Chicago house music (it’s “Distant Planet,” by Fingers, Inc.), Love responds like he’s in love, in the club. Then he bursts into time steps and other classic tap gestures, as if his purple-shod feet are fingers on that MPC. They are foot notes, embracing the trammeled history of tap and rocketing it into the future for everyone to see.

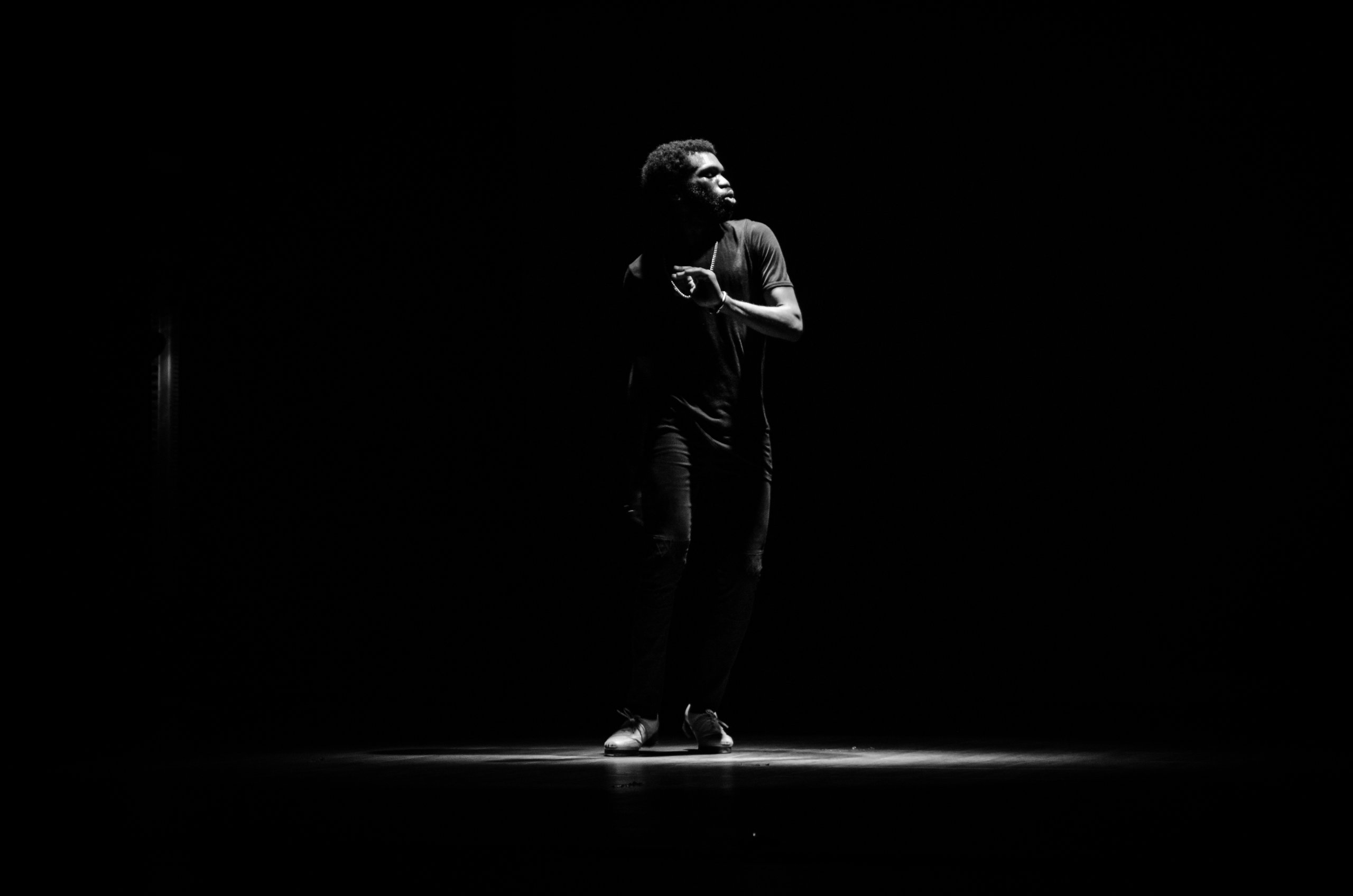

Love’s work confronts a dance form with a complicated legacy. A mix of hip-hop, vogue, ballroom, and other genres, his mash-up of maneuvers defies expectations of a tap performance, embodying narratives about race, gender, queerness, and identity. Often performing with his back to spectators (a subversive act favored by Miles Davis, who regularly faced his band while he played) and tapping until sweat saturates his clothes—a spectacle that the theorist and curator DeForrest Brown, Jr. described to me as “transformative Black masculinity”—Love obliterates the power dynamic between audience and performer, making space for both parties to look inward, and to reflect on whatever his dancing conjures up.

“He’s not only a tap dancer, but a scholar who is contextualizing the practice as a practitioner,” says artist and filmmaker Tiona Nekkia McClodden, who, along with Love and the actress Maysoon Zayid, is currently an arts fellow at Princeton University. McClodden featured Love in her 2022 exhibition about Black dance, “The Trace of an Implied Presence,” at The Shed in New York. There, a wooden tap-dance floor sat ready for use before a full-length mirror and a film she made of Love discussing and demonstrating his work.

In the film, Love beatboxes the rhythm of Sade’s R&B masterpiece “The Sweetest Taboo,” then performs a cover version of the beatboxing with his feet. He toys with percussive preconceptions, sometimes contemplating the track’s sultry vibe and sometimes fucking with it. At a live performance in the space soundtracked by Larry Heard’s mournful “Missing You,” he found, and took, similar liberties. Dressed in white, Love seemed to almost duet with himself, moving between and within tap’s formal conventions and the ecstatic bodily responses that house music inspires, from vogue poses to fabulous swooning. It’s startling. “There’s something a little taboo [about] tapping,” McClodden told me, “because of the way it’s been marginalized in the larger Black dance canon and stuck in its history.” Love doesn’t shy from the sweetness, or the bitterness, of that taboo. In doing so, he sets the movements free.

“I grew up in the era of noise and funk,” says Love, 35, who spent his childhood in Germantown, Maryland. “My parents built these amazing LP collections. They were always playing original-issue Janet Jackson.” He wasn’t particularly athletic, and preferred theater and Sesame Street as a kid. At the time, one of the show’s young stars, Savion Glover, taught its puppets to tap, and would later bring a fin-di-siècle hip-hop swagger to the dance form in the 1996 Broadway juggernaut “Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk.” Love watched Glover make the world his dance floor, and decided he wanted to, too.

To harness that energy, his mom put him in a local dance class that taught jazz, ballet, and tap. “My first dance teacher was Black, but most of the students were white,” says Love, who was usually the only boy in the room. “My mom wanted a different situation for me.” She urged him to audition for the Tappers With Attitude Youth Ensemble, a multicultural company co-founded by Renee Kaufman Kreithen and Yvonne Edwards (the latter of whom directed the company with Lisa Swenton-Eppard and Victoria Moss) in Washington, D.C., whose gifted hoofers regularly performed at places such as the Smithsonian museums and the Kennedy Center. Eventually, Love was invited to join the group, and swiftly moved up its ranks. “It was a very formative experience,” he says. ”They teach you basic tap-dance routines, like the shim sham, and also give you history.” He also met other dancers, such as Baakari Wilder and Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, who are now celebrated as virtuosi in their field. “I saw them establish their careers,” Love says. “They were possibility models.”

Adulthood brought the realities of tapping as a profession further into focus. In 2006, Love started his own company, the still-extant Emerson Urban Dance Theatre, while a freshman at Emerson College. “I was really into Janelle Monáe,” he says of the singer, whose passel of Afrofuturist funk records detail her cyborg, queer visions. “My friends and I would go into a rehearsal studio and create narratives of, like, robots. We rented venues. I taught myself how to lead a cast, put a concept together, do the marketing. That’s how you get your experience.” After graduation, he moved to New York and auditioned for a while. “I booked some theme-park work,” he says, with a sigh. “I was making a regular check. I was dancing.” An injury took him off that circuit and back to D.C., where he found a job in the communications department of the Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company. But he wanted to dance again. Love heard of a company in Austin that was looking for a principal dancer. He applied and got the gig.

A year later, he and the multiracial company were rehearsing a piece for the upcoming season. “It was a classic tap work by a Black choreographer, who has since passed on,” Love says. “The one person who knew the dance was teaching it to the rest of us.” At one point, Love looked up from his steps and saw the white director of the company in the hallway. “She had decided it would be a great idea to shoot promotional images for the show with half of her face covered in black paint. It was … unbelievable.”

But not unprecedented. Tap’s past is a cacophony of minstrel shows and blackface, originating in 19th-century America. “Tap is a Black art form,” Love says. “It comes from enslaved people on plantation fields, [who developed it as a way to] maintain a connection to where they came from. That got co-opted”—the 20th century saw a more theatrical version of tap take center stage in variety shows, vaudeville, film, and Broadway—“but even on the Hollywood lots, there were people like Mable Lee and Bill Robinson.”

Brown, Jr., the theorist and curator, who has traced the history of Black cultural production in his book Assembling a Black Counter Culture, shares that sentiment. “Tap started out as ancient rituals,” he says. “And then white men put on black face paint to mimic it, without knowing the incantations that they were summoning. Then Black people took it back, and put on European tuxedos. It’s part of the idea of making Black men human.” The dance form lost steam after the Second World War, and while still evolving, is far from its once-ubiquitous peak.

Back at rehearsal in Austin, Love decided it was time to make a different kind of work. “We’re all still plugging into that nineties moment of Savion Glover dancing to the music of his heart,” Love says. His heart needed other outlets. He began gravitating toward different forms Black dance music, including house and techno. He studied the shapes and strategies of queer revolutionaries in the worlds of vogue and ballroom.

Dancers from those realms confronted a double standard, according to art critic Ricky Tucker, who has studied New York’s vogue, house, and ballroom communities. “As a kid in the eighties, I was very aware that you could just take Coke bottle caps and press them into your shoes,” he says. “And then you practice until you make it or whatever. There’s upward mobility. And yet there’s a chasm between the reality of Black men being endangered, being jailed and murdered, and them onstage at Carnegie Hall.” The ’90s Glover, Tucker continues, embodied this contradiction. “He was trying to bust out of something—he’s got a ferocity,” he says. “Vogue offers fierceness. It’s drama and narrative building. It’s a femme effect.”

For Love, it was a revelation. “I was starting the process of figuring out what it means for me to be six feet tall, lanky, and queer,” he says. “In dancers like Willi Ninja, [the “Grandfather of Vogue”], I see self-affirmation. In house music, I hear Black queer history. I began thinking about how to create landscapes for me to live in. And how to create moments for me to bring in the training that sits in my body. What happens when I set up this environment for myself?”

These were artistic questions, but also literal ones. Tap interacts with its material conditions in ways other forms of dance don’t. Its alchemy of aesthetics and physics, of flesh and metal, transforms space not just in the metaphorical and metaphysical ways of all art, but literally. Tap turns wood to dust. It turns floors into a record of what happened—the shuffling, the dragging, the striking, the stomping, the drops of sweat, and perhaps, expectoration—and then, with a drop of a foot like a needle into a groove, transforms them into a record of rhythmic invention.

Love has since expanded his practice accordingly. He travels with a portable sound system and wood flooring that he makes himself, allowing him to perform practically anywhere. He’s working with the film-based artist Ariel René Jackson, devising dance floors that swap out traditional hardwood for soil and sugar. He’s jamming with Brown, Jr., who, as the audio producer Speaker Music, makes dexterous techno that investigates the form’s sonic and sociological complexities. And with lockdowns over for the time being, Love is planning to stage the third and final part of his 2017 work, “The AURALVISUAL MIXTAPE Collection.” “[The show] is based off an idea of ancestral knowing, or knowledge that’s passed along from generation to generation through rhythm and song and movement,” Love told an interviewer, underscoring the value of paying attention to ideas past. “It makes sense to go through different periods of time, to think about what was happening, what Black cultural production looked like in each of those eras, what topics were being talked about.”

The statement recalls that pandemic livestream project: As Love sweats through his suit, his feet tapping out the lines between his ancestors and progeny, the woman’s voice returns. “As we travel, you may encounter new personal discoveries or realizations,” she says. “If you can, jot these down or commit them to memory. Upon our return, we invite you to share these with those who you hold dear, so they may join you on your next trip, and be more prepared.” Love is showing us what’s coming next. We just have to be ready.