Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect (Yale University Press) is about absence as much as it is about the presence of its protagonist. Organized by the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania, the 336-page book of essays and photographs is forensic, collecting things that are ineffable: demolished structures, gaps in a fragmented archive, and a figure missing from the architectural canon.

Slightly older than the much more celebrated architect and engineer Julia Morgan, the first female architect licensed in California, Nichols (1862–1949) is considered the first American woman to establish her own independent architecture practice—a feat accomplished without generational wealth or the financial support of a husband in 1888, a time when professional paths for women were narrow. Although Nichols later married Reverend William Ichabod Nichols, the book opens with a note explaining the editorial decision to refer to the architect as “Minerva” rather than to define her by her married name (moving forward, I’ll do the same), and for clarity: 53 of the 81 known projects she worked on were commissioned before her marriage.

This produces an immediate familiarity, albeit one not without discomfort. It’s laughable to imagine a history of Minerva’s contemporaries—men such as architect Frank Furness (later a favorite of Robert Venturi) or Warren Powers Laird, architect and dean of the School of Fine Arts of the University of Pennsylvania—discussed as “Frank” or “Warren.” Yet as names go, hers is fitting, shared with the Roman goddess of handicrafts, the professions, justice, and wisdom.

When Minerva hung out her own proverbial shingle, at 26, she already had a decade of experience. She worked steadily, designing nearly 80 known projects—primarily residential—across her career. In the book, a photograph of her Philadelphia office, circa 1891, shows the architect bent over a drafting board. It serves as a frontispiece for “The Elusive Archive,” a foreword by architectural historian Despina Stratigakos. Best known for her 2016 provocation Where Are the Women Architects?, Stratigakos’s question gets only a partial answer from this image.

There’s evidence of productivity, for sure. Visible are sketches tacked to floral-patterned wallpaper and rolled drawings tilt against a curtained window frame. Propped up on the table is an elevation drawing of the Queen Isabella Association Pavilion at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (also known as the World’s Columbian Exposition). Minerva’s Spanish Colonial design for the suffragette organization, which she began in 1890, would have been her most public and prestigious commission at the time, but it was never constructed.

And yet, the sepia-toned composition, taken from the pages of Home Maker magazine, also evokes absence. Our heroine sits on the far left side of the image—a youthful long braid runs between her hunched shoulders, and her face is turned from our view. This is a portrait of an interior, not of an architect.

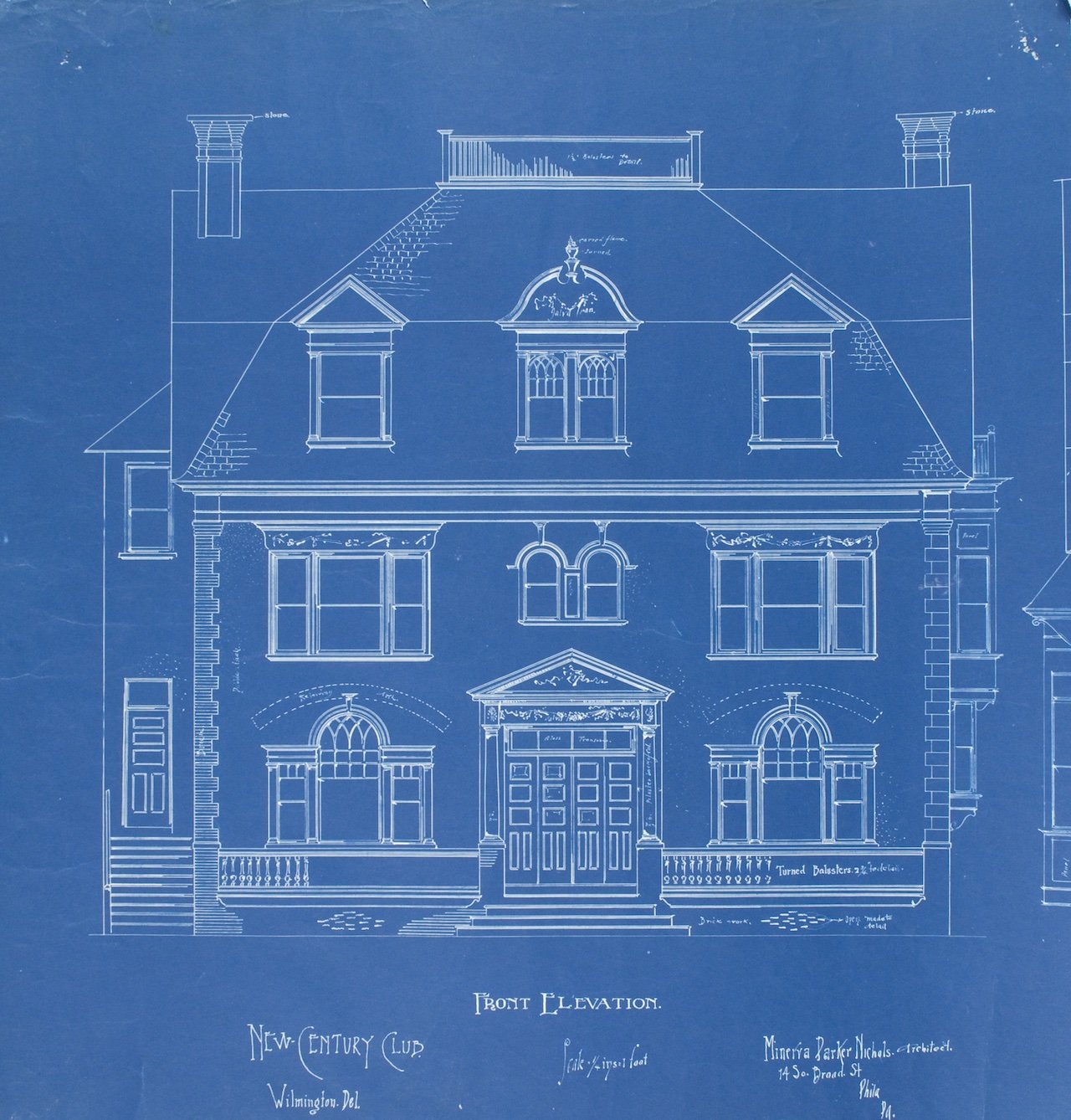

Although she would go on to design the Women’s Reception Rooms for the Chicago World’s Fair and New Century Clubs in Philadelphia and Wilmington, other women’s buildings aligned with the suffrage movement, the bulk of Minerva’s known work consists of handsome middle- and upper-class homes in and around Philadelphia. Her Colonial Revival and Queen Anne designs feature an array of stylistic gestures and domestic flourishes: dormers and turrets, wraparound porches, and Palladian windows. They’re more pragmatic than flashy, perhaps a function of her Unitarian beliefs. Style aside, her oeuvre reflects the growing agency of women as clients, users, and experts of architecture.

The book stems from a 2023 exhibition, also organized by the University of Pennsylvania’s Architectural Archives, and includes a robust catalogue raisonné by curator and collections manager William Whitaker. It also contains a visual portfolio by architectural photographer Elizabeth Felicella, who documented Minerva’s remaining buildings between 2019 and 2022. The book’s team submitted 248 images of Minerva’s work, comprising 32 sites, to the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), a program managed by the National Park Service that houses its collection at the Library of Congress. These sections not only redress historical gaps, but also record and preserve the work for future generations.

An extensive biography by Margaret (Molly) Lester and a collection of the architect’s writings for the Woman’s Journal and Housekeeper’s Weekly bookend the archive and portfolio. The book’s final section includes the essay “Women as Architects” (1896), penned by Minerva for the General Federation of Women’s Clubs’ Third Biennial, in which she appraises her contemporary profession and approvingly notes that women were now “practicing in almost every state in the Union.” She concludes with a call for solidarity: “So much work must be done to convert the crude material of mind and matter into beauty of form and spirit, that we are all co-laborers and not competitors.”

No stranger to the world of labor, Minerva’s writing resonates across centuries. She began working as a teenager to help support her twice-widowed mother and older sister. She studied at the Philadelphia Normal Art School, then enrolled in the Franklin Institute Drawing School, where she zeroed in on architecture, and apprenticed in Edwin W. Thorne’s small architecture office before venturing out on her own. Still, it’s necessary to acknowledge that the women addressed and fellow architects referenced, such as Louise Blanchard Bethune (who shares a distinction with Minerva as the first woman to run her own practice, though the book argues that Bethune operated the firm with her husband; other accounts vary), are all white, educated, and of a socioeconomic status necessary to reach professional standing.

Contributions by Lester and archivist Heather Isbell Schumacher emphasize the current need for an unflinching, intersectional reckoning that faithfully retells Minerva’s personal history while putting it in the context of the a country growing, colonizing, displacing, building, rebuilding, and extracting in the decades after the Civil War and Reconstruction. “We are once again living through a time of social change and upheaval,” Schumacher writes, “and the process of reexamining our past in order to build our future is challenging and often painful.”

Lester deftly condenses more than a decade of academic research in her biographical essay “Finding Minerva.” She paints a portrait of an ambitious designer aligned with the women’s rights movement, propelled by circumstance towards fiscal independence, and is careful to point out that Minerva’s success was earned within an unequal milieu.

In discussing the designer’s work for women’s clubs, Lester writes that Minerva worked “exclusively with white clients, both as individuals and as members of these segregated organizations.” And continues: “Given that her career coincided with the Jim Crow era’s constraints on space, education, capital, and property, this [clientele] is unsurprising. There is no evidence that this absence in Minerva’s portfolio was driven by explicit animus, nor is there any record of her acknowledging it or trying to correct for it. But the groundbreaking opportunities that she seized for herself and extended to many other women were not available to all women—and were entirely forbidden to some.”

One of Minerva’s most important projects was the New Century Club of Philadelphia, an organization established to support the “interests of working women.” She began working on it in 1891, the same year she got married. (Minerva continued to practice after she wed and had children, remaining engaged in architecture until her last project, in 1936, though the astounding pace of her production slowed as she took on tasks as wife, homemaker, and mother.)

Distinguished by a brick edifice punctuated by a pastiche of arched and bay windows, behind which civic and charitable causes were taken up in assembly rooms and parlors, the club stood at 124 South 12th Street in Philadelphia until 1973, when it was demolished due to dwindling membership. Before the wrecking ball, a series of black-and-white photographs were made by George A. Eisenman of the building and its interior, and submitted to HABS for posterity in lieu of restoration. (They can be viewed on the HABS website.) The National Historic Preservation Act was established in 1966 in the wake of the destruction of Penn Station in order to save buildings, but the Philadelphia Historical Commission considered the structure “obsolete,” allowing it to be razed.

Felicella, the contemporary photographer, used the images as inspiration for her documentation of Minerva’s work. Following the organization’s technical requirements, she used a large-format view camera (a 19th-century 8x10 Deardorff) and black-and-white negative film, which gives her compositions an atemporal quality countered only by a smattering of modern-day street signs, automobiles, and furnishings. Plate 9, a detail of a stair landing in Mary Potts House, completed in 1890, reveals a pair of built-in linen drawers dated only by a broken brass pull.

Felicella’s photographs depict both the massing and façades of Minerva’s structures and their interior intimacies, such as mute closet doors, glazed fireplace hearths, burnished handrails. Minerva herself discussed how female architects were well suited to this indoor landscape, writing that, “If home is a woman’s sphere, it must be admitted that she should build the home which she is to tend with such care.” But it could also be argued that interiors are not solely aligned with gender; they offer a place of expression for those marginalized in civic space.

That kind of expansive way of thinking permeates the book. The Search for a Forgotten Architect doesn’t wholly find and claim its subject—as if she were a suspect on the run, or a rare butterfly ready to be pinned. Instead, the book’s contributors suggest the many ways that one corrective begets another, leading to a long line of births and repopulations across time.

The book Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect will be the focus of the April 4 gathering of the New York Architecture + Design Book Club, a quarterly book subscription and event series organized by Untapped and the Brooklyn bookshop Head Hi. Book contributors Heather Isbell Schumacher, Bill Whitaker, Elizabeth Felicella, and Margaret (Molly) Lester, along with interior designer Loren Daye of the studio LoveIsEnough, will lead the program’s interactive discussion. Find out more and RSVP on the book club’s website.