This past summer, Barbie Dreamhouses sprawled out across our collective imagination like a rose-colored suburban subdivision. They feature prominently in Greta Gerwig’s movie, where a solitary Barbie occupies each multistory home. Notably wall-less and stair-less (who needs a staircase when a spiral slide will do?), the toy houses reflect vast expansiveness—in pink. Boundless, they combine manifest destiny, the American dream, and a pop feminist utopia. If Virginia Woolf wanted a room of one’s own, Barbie craves the world.

Even without stirring up a subtext of the consequences of globalized consumerism, Barbie’s supersize fantasy crashes against real-world concerns. Sky-high housing costs and a need for sustainable solutions in the face of the climate crisis suggest that a compact footprint should be the norm.

Such a shift shouldn’t be understood as reactive nor simply efficient. By valuing small spaces, we find pleasures through design more generous and more humane than solutions made for bigger projects—adding to the case for living with less. We can also find opportunities for renewed intimacy. Literary critic Susan Stewart compares the tiny, enclosed rooms of a dollhouse to the secret recesses of the heart—a stark contrast to the outward-looking Dreamhouse. “Center within center, within within within,” she has written. “What we look for is the dollhouse within the dollhouse and its promise of an infinitely profound interiority.”

That “profound interiority” resonates—particularly in a post-pandemic, sometimes-work-from-home moment. Small homes (houses and apartments alike) must accommodate a seemingly infinite number of overlapping functions: dinner parties, yoga mats, and houseguests among them.

Architect Michael K. Chen calls this phenomenon a “choreography of the body.” MKCA, his New York City–based firm, cut its teeth figuring out how to pack a rich life into just 400, 300, even 200 square feet. “The point was to try to say yes to as many possibilities as one could imagine,” says Chen. “We would make these really fun lists of all of the ‘unreasonable’ things clients wanted to be able to do at home”—and then design a wealth of adaptations. (“Unreasonable” is as subjective as beauty. Hosting a dinner party for eight in a studio apartment is infinitely reasonable when you design for it.)

MKCA’s Unfolding Apartment, for example, is a study in flexibility. A bright blue cabinet is the central hub of a 400-square-foot Manhattan studio. As if performing a choreographic score, it pivots and flips throughout the course of the day. Spaces for living, entertaining, and sleeping are activated as a Murphy bed is unfolded or a screen pulled out to create a work area. “We look for a bit of spatial constraint,” says Chen. “We don’t like it when a space gets too diffuse. There’s a kind of social charge that happens with a little bit of compression in the right place.”

While a dynamic approach to multiple uses unites the small-scale renovations in his practice’s portfolio, Chen notes another common thread: In almost every case, clients had lived in their homes for years before searching out an architect. These modest apartments were in neighborhoods that had become very desirable over time and the units, cogs in the machinations of New York’s real estate market, were increasingly valuable. Thus, an investment in good design allowed residents remaining in a particular location to maximize all the imaginable ways to occupy minimum square footage.

And yet, inhabiting small spaces shouldn’t be viewed as an extreme sport, either in terms of livability or real estate. What we think of as “small” often falls along a spectrum of minuscule to cozy, with those poles defined by cultural, geographic, and fiscal constraints. The 2022 American Home Size Index notes that, in 1949, the average size for a new single-family home was 909 square feet. By 2021, that figure had ballooned to 2,480, with large home construction in rural and western states such as Colorado and Wyoming contributing to the rise.

One of my books, Tiny Houses, focuses on homes under 1,000 square feet. That figure was basically the difference between average American home sizes in 1970 and 2004. Published in 2009, the book was a reaction to Sunbelt McMansionization, which went belly-up in the subprime housing crash. Then, downsizing became an economic necessity for those impacted, who lived mostly in the suburbs. Today, it’s widespread, as cities advocate densification and home buyers and renters feel the pinch. Small spaces in denser urban conditions are increasingly the reality—in the States and globally—and demand a contemporary rethink.

In valuing smallness, we must embrace object lessons in intimate interiority. While Chen emphasizes how high-performance furniture might adapt to the movement of bodies, artist J.B. Blunk’s handcrafted cabin demonstrates beauty in its all-encompassing, resourceful design.

Blunk, a prolific sculptor, passed away in 2002. His home, tucked among pines in the hills of Inverness, California, overlooks Tomales Bay. He and his first wife, the artist Nancy Waite, constructed it from 1958 to 1962. Made from reclaimed lumber from across Marin and Sonoma counties, the home is luxurious in its relationship to place. Redwood boards and other materials were salvaged from ramshackle barns, chicken coops, and abandoned train stations.

“This was not an aesthetic decision, but rather an economy of means,” says Mariah Nielson, who preserves the home as an art space. “Because they lacked financial resources, the house took many years to build, and this allowed J.B. and Nancy to take their time developing specific details and contemplating the space as it slowly came together.”

At 1,400 square feet, the design doesn’t require the same flexibility as a more compact interior, but as a small space, it expresses its personality in the details. Blunk considered it “one big sculpture.” He designed practically everything, at all scales, from the overall structure to the built-in furniture and cabinetry to the ceramic mugs. Such details as light pulls whittled from wood scraps and a carved kitchen sink rubbed smooth by time not only show the artist’s hand, but act as studies in touch, texture, and surface. The sliding front door is made from a single slab of salvaged old-growth redwood. According to Nielson, it groans with a tremendous, visceral sound when opened.

“The patina of a handmade home and its layers of history create a very special energy, which is palpable and sometimes visible: all the marks in the kitchen table, the polished bishop pine door handle,” says Nielson. “Even though the home is small, it provides everything we need and is a delight to live in because it was built with such consideration and playfulness.”

“When we talk about the value of a small space, it is personal,” says Marina Quiñónez, senior architect for Los Angeles’s Bureau of Engineering. In 2021, the city opened its first tiny house village as part of the A Bridge Home initiative to shelter individuals and families experiencing homelessness. Chandler Boulevard Bridge Home Village in North Hollywood is just one of 10 built (and 17 total planned) in a county with upwards of 70,000 unhoused people.

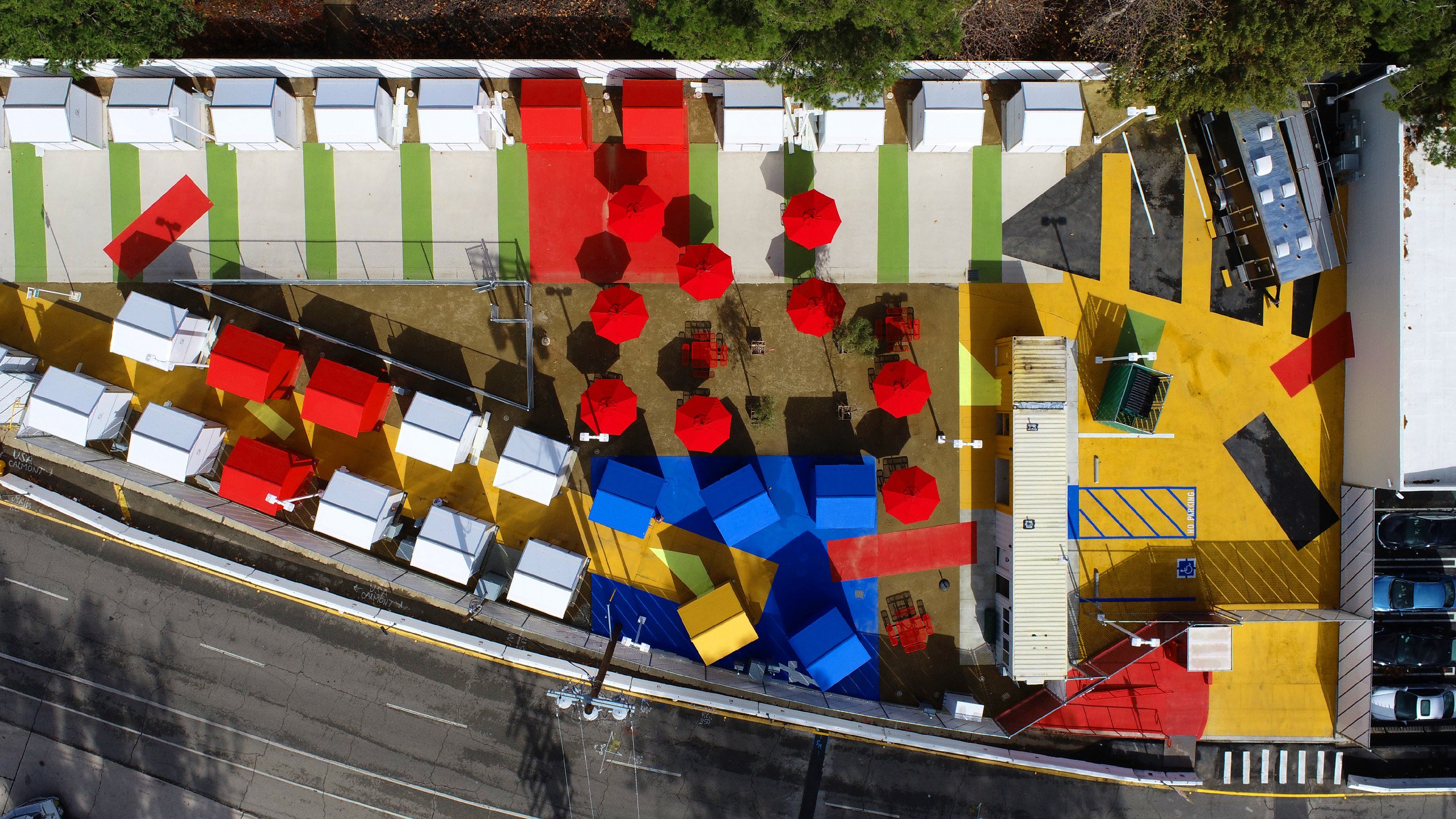

The BOE partnered with Seattle-based company Pallet Shelter, which designed the micro homes, and local firm Lehrer Architects. Operated by the nonprofit Hope the Mission, the project’s 40 identical homes are meant to be temporary, with residents staying months not years, but considerations of how one might express identity and have a feeling that goes beyond institutional care were important.

The prefab Pallet homes measure just 64 square feet and look like cartoon houses: four windows and a door. Inside are two beds, some shelving, and air-conditioning. The architects painted the outdoor asphalt and façades in swaths of bright red, blue, white, and yellow to distinguish pathways and individual units that would otherwise evoke widgets in a parking lot. Quiñónez notes that the color gives residents a sense of ownership within a greater community.

“The biggest thing with these tiny home villages is that the small space becomes theirs,” continues Quiñónez, describing how residents place flowerpots outside their doors to individuate their residences. She shares that some decorate inside with string lights and posters. A single mom housed with her kid might have Transformers-themed bedsheets. “They can close the door, which brings safety as well. Large-scale, congregate shelters don’t allow for that kind of personalization.”

Complete with communal facilities for bathing, dining, laundry, and support services, the homes at Chandler Boulevard embody the basic tension of all cities between interior and exterior, between what is private and public. This holds true at any scale. “Designing these little communities is basic urban design,” says Deborah Weintraub, chief deputy city engineer at the BOE. “We did all the things you would do if you were asked to design a city, knowing that our building block was this eight-by-eight tiny home. There is a clear hierarchy to the layout—between the separate paths, the gathering space, and the entrance.”

Chen is also using his expertise in designing small spaces on behalf of people who are most in need. During the pandemic he started Design Advocates, a nonprofit network of architecture firms committed to social equity. He’s currently working with the mayor’s office in New York to evaluate how to convert existing buildings into shelters. He echoes Weintraub’s idea of a city within a city when discussing how to design common kitchens and shared amenities to support friendship and kinship, and he also stresses the importance of connecting to a surrounding neighborhood. A room of one’s own may offer a rich inner life, yet we are forever coupled to the wider world.

Ultimately, designing in small spaces is about bridging the intimate interior and the greater urban environment. This means creating flexible, adaptable places that offer immeasurable benefits—they expand and enhance the way we live.