The state of design and its intersection with the science of human experience.

When Susan Magsamen’s two-year-old granddaughter needs a nap, she brings her to a quiet room, pulls down the blackout curtains, and turns on a white-noise machine, creating the just-right setting to comfortably lull her to sleep. This type of ritual will sound familiar to caregivers of young children, but Magsamen wonders why, for the most part, we neglect how our environment makes us feel as we get older. “There are very specific things that create the conditions for a kid whose nervous system is really wound up to rest,” she says. “We don’t apply those things to us as adults. We override them and override them, and then we get sick or get stressed or we stay stressed.”

Magsamen is the founder and executive director of the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University, a research group that studies neuroaesthetics, a field whose name was coined in 1999 by neuroscientist Semir Zeki that explores how we perceive the world around us. She’s interested in bridging the gap between this body of knowledge and how designers are shaping our world. “We forget to listen to our bodies,” she says. “And when you start to listen to your body, you make very different decisions.”

Science has long influenced design, from germ theory in the 18th century, which gave rise to urban sanitation systems, to the mid-20th-century development of ergonomics that catalyzed the idea of user-friendly design. As knowledge about how our bodies relate to the world becomes more comprehensive, the spaces we inhabit and the objects we use begin to reflect those insights. It’s why our cities have parks, our offices have task chairs, and hospital recovery rooms have ample daylight.

Now, neuroaesthetics has advanced to the point where it is uncovering the mysteries of the brain, the most complex organ in the human body. Thanks to new, highly detailed imaging, researchers can map what’s happening inside us down to the scale of a neuron, offering a more sophisticated understanding of human experience. Architects and designers are now translating those findings to the built world with the ambition to create more spaces that help us flourish.

Suchi Reddy, an architect based in New York and the founder of the firm Reddymade, has been integrating neuroaesthetics into her work for more than a decade, from residential interiors to retail design to public art installations. Her philosophy? Form follows feeling. She has described neuroaesthetics as something that unlocks the magic of experience and can help architects make more enriching spaces. “We know how to design prisons to make people feel bad,” Reddy says. “The design of the rest of the world is, however, not geared toward making people feel good.”

The application of neuroaesthetics to the designed world has a name: neuroarchitecture. It’s an alienating, jargony phrase—even to its early adopters, like Reddy. “I prefer the term neuroaesthetics, because it is a much truer term in describing a complete embodied reaction to both environments and experience,” she says. “Neuroarchitecture implies that architecture is separate from a holistic experience of the world, which includes much more than architecture, like landscapes for example. Just adding ‘neuro’ to a word—whether neuroarchitecture or neuromarketing—seems specious to me.” But at its heart, the concept is an extension of user-friendly design principles, which largely focused on legibility and ease of operation. It goes a step further to take what we feel into account. To Magsamen, it’s “a way to optimize space for humanity, not just purely for function.”

So far, the growing body of research has shown that spatial experience is shaped by biological and social factors. We’re drawn to legibility but also crave complexity. Elements from the natural world, like plants and certain shapes, are also appealing. Meanwhile, color has deep cultural symbolism that can evoke specific feelings.

Having agency in our environments is important, too. Researchers are eager to share their work with designers who can translate these findings into the real world. “What we think we can do is create a cupboard of aesthetic ingredients that say, ‘If you’re designing for X, and these are the variables that you need to consider, these are some things that we know about light, sound, and color that you can put together to help enhance or increase the likelihood that you’re going to meet the emotional space required,’” Magsamen explains. “But it’s not one size fits all.”

Over the past decade, the field of neuroaesthetics has gained more recognition. There are a growing number of research groups that are dedicated to the field, such as Magsamen’s Arts + Mind Lab, the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, the Urban Realities Laboratory at the University of Waterloo, the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, the International Centre for NeuroArchitecture & NeuroDesign, The Happiness Research Institute, and the Conscious Cities Movement. The field’s insiders are at the point where they want to bring more people into the fold in order to create more demand for this type of design. The first step is getting our attention.

“People don’t realize that their environments are having the profound impact on them that they are,” says Sarah Williams Goldhagen, an architecture critic and the author of the 2017 book Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives. “And they don’t realize it because they don’t know enough about how human experience works. We are animals. [Some of] our habitats nurture and support growth and well-being, and some don’t. In the United States, there’s more of a sense of feeling that these things are just sort of neutral backgrounds that don’t have any effect on us.”

Colin Ellard, a neuroscientist at the University of Waterloo and author of the 2015 book Places of the Heart: The Psychogeography of Everyday Life, has examined how the built and natural environment affects how we think and feel. He notes that while conversations about building practices and health have led to widespread acceptance around physical health, the effects on our psyche are just beginning to gain traction. “We talk about ‘sick building syndrome,’” Ellard says, referring to a phenomenon where people become ill from inadequate ventilation and contaminants in the air. “A building can be psychologically sick as well.”

Getting architects and designers, who would presumably tell their clients about the importance of designing for experience, on board with the approach has faced roadblocks. “A lot of the people who are tenured in schools of architecture are almost actively hostile to [neuroaesthetics] because they don’t know anything about it,” Goldhagen says. “It would require them to learn a whole different body of knowledge than what they know and feel comfortable talking about. Cognitive neuroscience, and sciences in general, are a bit threatening, too, because architects want to think of themselves as creators and artists. And science sounds like, Oh, you’re going to give me a set of rules.”

However, this attitude is changing. Discussions around mental health and neurodiversity are mainstreaming, which is creating friendlier waters for neuroarchitecture. “It’s not a taboo subject anymore,” says Khoi Vo, the CEO of the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID). “It’s really important to understand all aspects of design, not just the physical, but emotional and mental wellness, too.”

Designers who are embracing the experiential approach to architecture compare it to the nascent days of universal design, a movement to make spaces accessible to all, and to sustainability. ASID’s trend report for 2025 emphasized the importance of neuro-inclusive design, or an approach to design that takes a diverse array of sensory needs into account. This could look like offices having a mixture of quiet and stimulating areas where employees can choose to work. “For us, it was really about, How do we include everybody?” Vo says. “How do we design spaces that can try to accommodate as many people as possible?”

Meanwhile, there are broader shifts happening in how designers view their roles that are contributing to the rise of neuroarchitecture. “I have always taught my students that design is inherently a discipline where you are in service of your clients,” says Vo, a former professor at the Savannah College of Art and Design and University of North Carolina Greensboro. “But you are responsible for making your clients aware of things that potentially can be beneficial or detrimental to a project. Informed designers see it as a responsibility.”

Informed clients, too. Competitive businesses and institutions—like hospitals, universities, and Fortune 500 companies—are integrating these principles to attract and retain talented individuals. While elite spaces are receiving the benefit of neuroaesthetics, designers and scientists view its adoption as a social responsibility. “When you dig deeper and find that there are physiological and cognitive components to a given design, then it’s harder to make the argument that it’s a luxury good,” Goldhagen says. “[Those components] become something that everybody should get.”

One area where neuroaesthetics can be a tougher sell is the developer community, which has a highly influential hand in our cities and spaces. A common challenge here, according to Ellen Buckley, founder of the real estate collective Prospera, is that real estate is a commodity that is traded, bought, and sold but that also plays a tremendous role in our everyday lives.

“How do we place value on something that has both a numerical value and a qualitative value to the people who live in it, who need it, and who require it?” Buckley says. “Have I seen plenty of developers in my world look at real estate as simply a commodity? Absolutely. Do I take that point of view? No, I do not.”

She is working on a mixed-use project in Florida with Reddy and the neuroscientist Andrea Chiba, and is excited to show how the developer community can embrace neuroarchitecture. “I’m proactively doing this because I see the opportunity and the value that we can deliver to people,” Buckley says. “It’s hard to convince people of a new idea without proving it to them.”

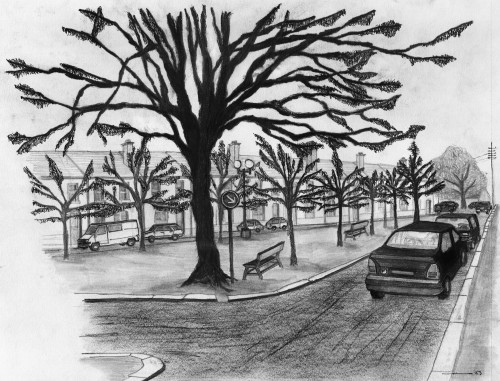

Policymakers are catching wind of neuroaesthetic principles, too, which may lead to wider adoption. Ellard, the University of Waterloo neuroscientist, is currently working with Canada’s ministry of Housing, Infrastructure and Communities to develop a handbook for the design of affordable housing. “I was sort of stunned when they approached me and said, ‘We want you to help us understand how psychological principles can inform policy,’” Ellard says. His lab is also researching complexity in urban environments, with funding from Heatherwick Studio’s Humanise campaign, an initiative to make buildings more joyful and engaging.

This summer, Magsamen is convening a conference to amplify the lessons of neuroaesthetics to influential companies in the design world, and is encouraged by increased interest in this work. At long last, she says, “the field is coalescing, the research is happening, and the practitioners are coming together.”