DATE↓

STORY TYPE↓

AUTHOR↓

Reaching the ideals we seek today doesn’t require going back to the land.

My mother threw away her copy of the Whole Earth Catalog long before I was born. Having endured so much use, it was in shreds, she tells me as I sit in the kitchen of her home near Golden, Colorado. She first purchased the manual when she was 14, growing up in the flower children era. She was deeply drawn to it, calling herself a devotée, she says, “because of the zeitgeist I was unconsciously a part of: that whole Aquarian Age,” prompting a “return to the earth.”

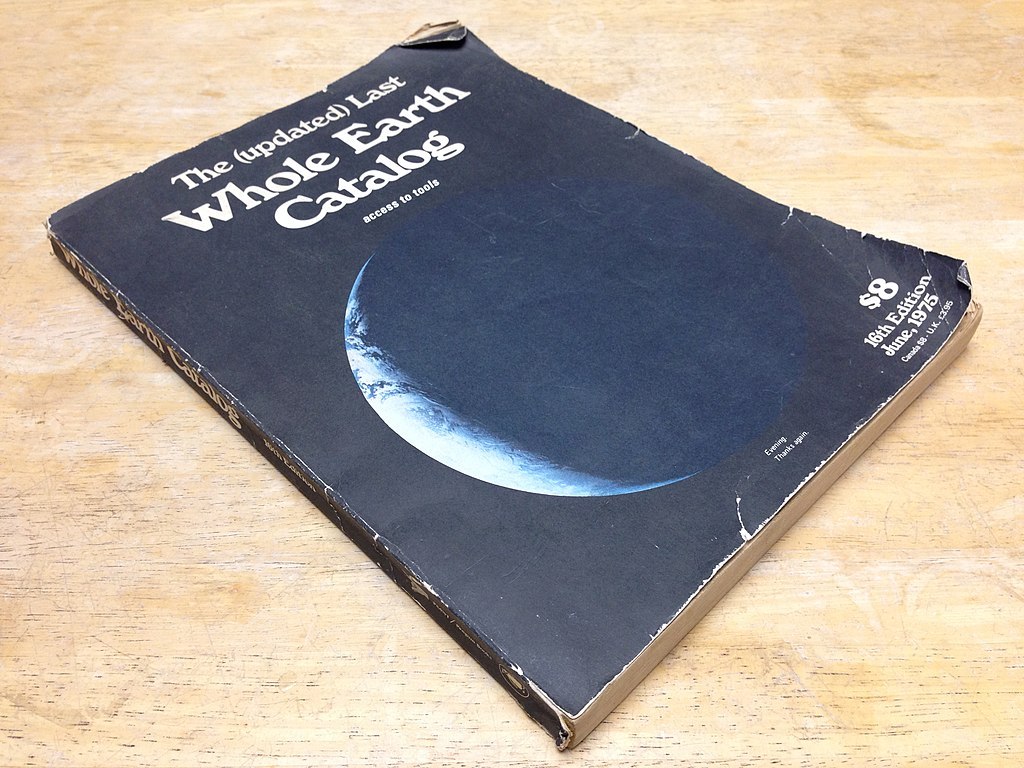

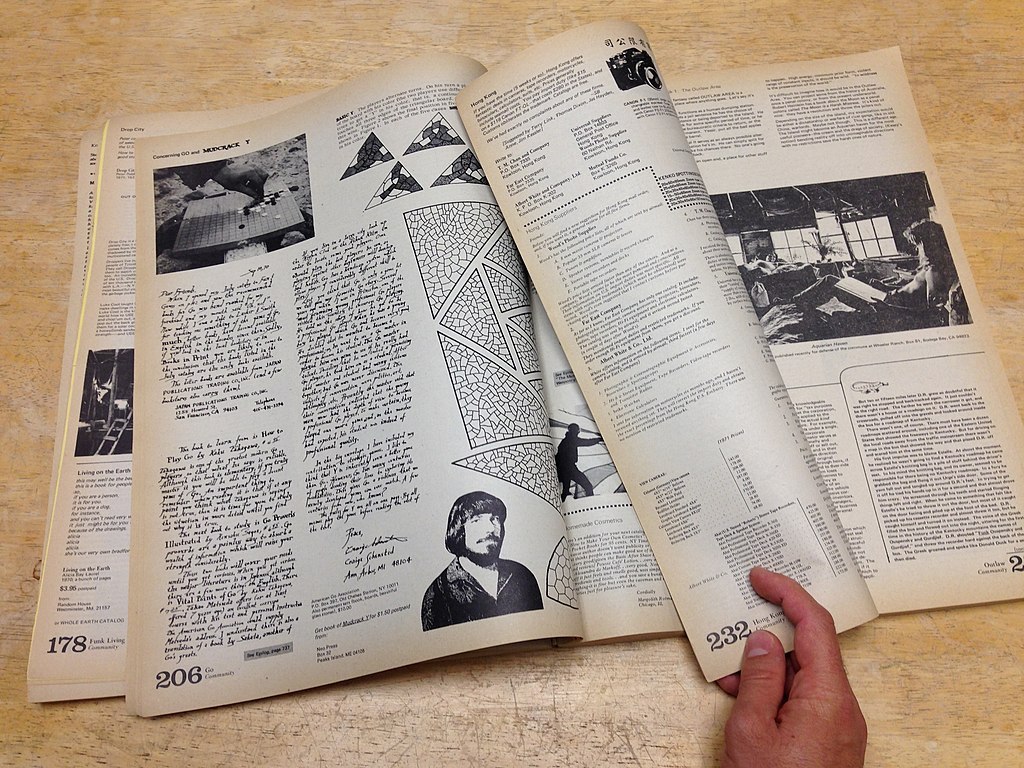

A compendium that reads like a scrappy, ad hoc Sears mailer, the Whole Earth Catalog featured products, books, and tips for those seeking a life defined by self-sufficiency. Published several times a year between 1968 and 1971 (and a few times afterward) by its technofuturist co-founder and editor, Stewart Brand, the volumes offered insights and instructions for tasks such as building geodesic Bucky Domes, constructing solar arrays, operating weaving equipment, and performing first aid. Received with great excitement by hippies and futurists, the catalog’s contents informed a social revolution characterized by experimental living communities and the age’s countercultural mantra to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” To my mother, the notion of going back to the land meant freedom: building a life on her own terms.

Open the first issue and you’ll find a commandment: “The user should know better what is worth getting and where and how to do the getting.” At the time of the Whole Earth’s emergence, what was worth getting was away—from a hyper-capitalist culture characterized by a Leave It to Beaver–esque, Buick-in-every-driveway pattern of consumption.

Last fall, more than 50 years after the catalog debuted, almost all of the Whole Earth library was digitized and made available online, for free. Newly accessible to younger generations, its readers can once again define “what is worth getting” for themselves.

In our current era—one defined by climate collapse, international conflict, and the decline of democracy—the question of the utility of the Whole Earth Catalog is fraught. Is it now simply an archive of a lesser-tech era, the subject of a mythology perpetuated by the unduly optimistic Silicon Valley–types who idolize its publisher while building their lavish bunkers? Can we ever fathom dwelling in self-sufficiency, or imagine a new path to utopia? I felt compelled to dig around for answers.

My parents didn’t raise my sister and me as Whole Earth children. We lived in a small suburb of Boulder, Colorado; not in a commune or “on the land,” by far. But there were elements of our existence that hinted at my mother’s past: A frequent shopper at Crystal Market natural grocers, she fed us seaweed snacks and bulgur, and enrolled us in children’s meditation classes. At 14, I began working for the local community garden’s youth program, where I spent every summer for the following four years learning about high-desert irrigation, growing organic produce, and how to operate an aging tractor, while selling our harvests at the farmer’s market.

There, in some ways, my mom’s adolescent Aquarian values began to resonate with me. As a teenager, she went to Ipswich High School—a “hippie school,” she calls it—and later attended the Habitat Institute for the Environmental in Belmont, Massachusetts (now called the Habitat Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary). Students there visited intentional living communities attempting to develop self-sustaining habitats in nearby places such as Cape Cod, where residents grew their food and farmed fish. In 1976, she moved to western Massachusetts to live on a New Age spiritual commune that was loosely affiliated with the Renaissance Community (once called the Brotherhood of the Spirit).

By then, my mom had been reading the Whole Earth Catalog for almost a decade (though the first Whole Earth issue, she stipulates, was far superior to those that came later). She loved them because they offered access—to information including recipes for granola (a novel food at the time), Japanese construction techniques, herbalism, and more.

They also offered access to people attempting to build a world aligned with self-sufficiency—most notably Buckminster Fuller and Paolo Soleri, whose dome forms were emblematic of communal life. In one issue, she read a review of the 1970 book Living on the Earth: a consequential guide for members of the back-to-the-land movement that was beautifully hand-written and -illustrated by 19-year-old Alicia Bay Laurel. My mother immediately purchased the book, and to this day, it remains one of the most influential titles in her life.

I contacted Laurel, now 74, to get a better understanding of the context from which her book emerged, and to hear how she thinks about it now. She told me she wrote it as a way to document what was necessary to survive while residing at Wheeler Ranch, a Northern California commune made notorious by neighbors who complained of drug use and unsanctioned buildings, and that housed dozens of residents who sought a life outside of cities and post–World War II American culture.

“All of a sudden, the United States was the most powerful country in the world,” Laurel says of the time. “And it wanted to not only stay that way, but increase its military. Everything was about consumerism.” The Vietnam War intensified as her generation became teenagers. “Here was this society,” she continues, “that was willing to grind up its young men and turn them into corpses.”

This horror, coupled with LSD usage, which Laurel credits for inducing a feeling of universal interconnectedness, spurred many to leave behind the structures and rules that would fuel a culture of violence. Building their own societies for living communally required skills that both Living on the Earth and the Whole Earth Catalog could teach. (Though similar in content—the former provides instructions, for example, for making soap and for building a kitchen in the forest—Laurel says that the books, “were related, but not the same.”)

“Stewart Brand was not particularly interested in living rurally and doing subsistence farming,” Laurel says. “He was more interested in information systems. The catalog, for him, was [about] trying to make available all the materials that people like me and my friends might find useful.”

Laurel lived happily at Wheeler Ranch until her book was picked up by Random House, in 1971 (its first version was released by Book Works, a small Bay Area publisher), and was made wildly popular by the Whole Earth review. She left Wheeler Ranch shortly thereafter, using her earnings to continue writing and making music.

Meanwhile, my mother didn’t stay long at the Habitat school. “People got in each other’s way, and not in a healthy way,” she says. “Some communes were like dictatorships, or more like cults,” while others, like hers, made decisions by consensus. She eventually returned to her hometown of Columbus, Ohio, and enrolled at Ohio State University to study social work.

On page 81 of the Whole Earth Catalog’s 1968 issue, to the left of a recipe for “beautiful natural grain cereal” is a letter from a reader, detailing the conflicts inherent to utopias. The author, known only as “ORO, El Cerrito, Calif.,” writes that he had spent more than 20 years in the “Hippie Movement,” living in communes “based on anarchistic freedom” as well as in ones “based on religion.” The communes based on freedom failed within a year, he notes, while “those communities based on authority, particularly religious authority, often endure and survive even against vigorous opposition from the outside world.” In other words, we could return to the land in search of freedom only to be met with failure; countercultural success requires replicating the same hierarchies found in society.

Laurel tells me that the problems in the communes that ORO mentions were inherent to experimentation. “All of those places were social experiments: whether we could provide enough food, enough whatever we needed, to live peacefully.”

While those social experiments, like many in the U.S., didn’t last, my mom maintains that the counterculture movement didn’t die off; instead, its values got baked in to our culture. The small-scale obsession with health foods, natural textiles, and naturopathic remedies can be found in modern mainstream grocery and hardware stores, and Amazon, YouTube, and Google can be thought of as extensions of the access provided by the Whole Earth enterprise. Reading the catalog today with any semblance of seriousness, I begin to feel not like a countercultural Aquarian but like a prepper, gathering supplies and honing skills in anticipation of an inevitable apocalypse, reading in order to shield myself and my immediate family from harm.

Such prepping feels eerily similar to living in a commune. I briefly lived in one outside Lyons, Colorado, after finishing college, in 2008. I was brought there by a Craigslist ad placed by a group of homesteaders seeking additional residents. I spent time on their land—dirt paths wound through dense coniferous forest; hand-built houses were surrounded by greenhouses, vegetable gardens, and animal pens.

It was a gorgeous place founded in darkness. The colony’s matriarch, an older woman who would zip around the rocky valley on an electric scooter, had established the mountain refuge under the shroud of “peak oil”—a theory that we would soon run short of fossil fuels, and be violently forced into civil war and agrarian life. She spoke of buying some yaks, which would someday tow obsolete cars that people would retrofit as wagons.

The thought of peak oil gave me slight shivers of paranoia at a time immediately preceding a global financial meltdown and amid a seemingly endless Middle East war. Returning to the land to manage the everyday struggle of staying alive seemed like a viable possibility at a time when the future felt inconceivable. Today, the concept speaks to me as a now vanished countercultural impulse: the longing to build something cooperatively out of care for each other and the planet—not out of fear—and despite communism’s pitfalls.

Maybe that’s what separates my generation’s desires from those of the Whole Earth–era audience’s: aspirations driven by fear and anxiety about the future, rather than an ethos of togetherness. Sure, those communes based on freedom generated conflict, and many failed, but perhaps the spirit of self-sufficiency was driven by a collective effort to build something better.

Laurel says that the idealism of the Whole Earth texts remains intact in global ecovillages, but what they and the rest of us—facing endless natural disasters, war, and illness—might deduce from the catalog today is the notion that building a community, like building a whole new society, requires skills and care.

This understanding entails recognizing that the failures of supposed utopias past—both those based in anarchy and those rooted in religious zeal—failed, in part, because of their separateness from broader society. (It’s no wonder we look at the visions of present-day technofuturists, with their bunkers and dreams of erecting new cities in the desert or on other planets, as a prepper’s heartbreaking wet dream. Rather than feeling liberating, self-sufficiency starts to look like a lonely endeavor.)

Instead, the “urban utopia” could be characterized by expansiveness: opening ourselves up to others and sharing our bounty and our safety without prejudice. We see glimmers of such ideals in our cities, where community gardens, tool libraries, mutual-aid networks, and other more informal methods of providing access are generated by our collective efforts, allowing everyone to share in what can be built from such resources. Rather than ignoring civic and structural ills, we must tackle them together. What we seek doesn’t require going back to the land, but rather going back to the cities and neighborhoods we live in now—and reorienting them around elements that serve us all.

“Once there’s a center, different kinds of structures grow from it, and they aren’t necessarily farms out in the country where middle-class kids are taking drugs,” Laurel tells me. Communal living doesn’t require a commune, but simply communing.

We might not be able to live as the Whole Earth and its followers intended. We might be better off embracing its mythology—its core ethos of access to skills and care—and building our own utopias right here.