When I arrive on site to document a building, there are several things I am hoping for: good light, a hot cuppa, and something indescribable that people younger than me would call “good vibes,” to name a few. But the first (and not least important) thing I hope for is that the building is actually finished.

This might seem like a given for someone who is paid by architects to photograph their work, but it’s not. The impact of trying to make work at an unfinished or unoccupied building is manyfold. There are ways to get around it for sure, but one thing that’s truly difficult to fake is the real, unstaged presence of people in that space.

I’m lucky in my job. I have seen a lot of completed projects, and so I have uncommon insight into the ways these spaces are populated and used after the architect has left the building. Recently, I made a film about a private home in the Scottish countryside, designed by the architecture studio Denizen Works, that included an 18-foot-high entrance hall with one express purpose: to hold an enormous Christmas tree when the time came round each year.

It is an amazing space with a beautiful gold-tinted light well, but I wonder about the other 11 months of the year, and all the ways the family will end up using the hall when it doesn’t have a Christmas tree in it. Maybe it will become a boot room of sorts? Or someone will fill it with plants, put a bench in there, or create a gallery of family photographs? It’s probably large enough to hold a badminton court. Do they even play badminton? Maybe a giant train set? All of the above, probably—I’ll never know—but it’s fun to imagine the possibilities that an open, free space in a home like that offers the people who live there. Not all architects consider those possibilities, or the importance of designing for them. People do not use the same spaces in the same ways.

On any given day on location, I’m chasing the first photo or film scene that makes me smile. Once I have the first one in the box, I can relax. Invariably that moment is a human one. I love to see the mess of life in architecture.

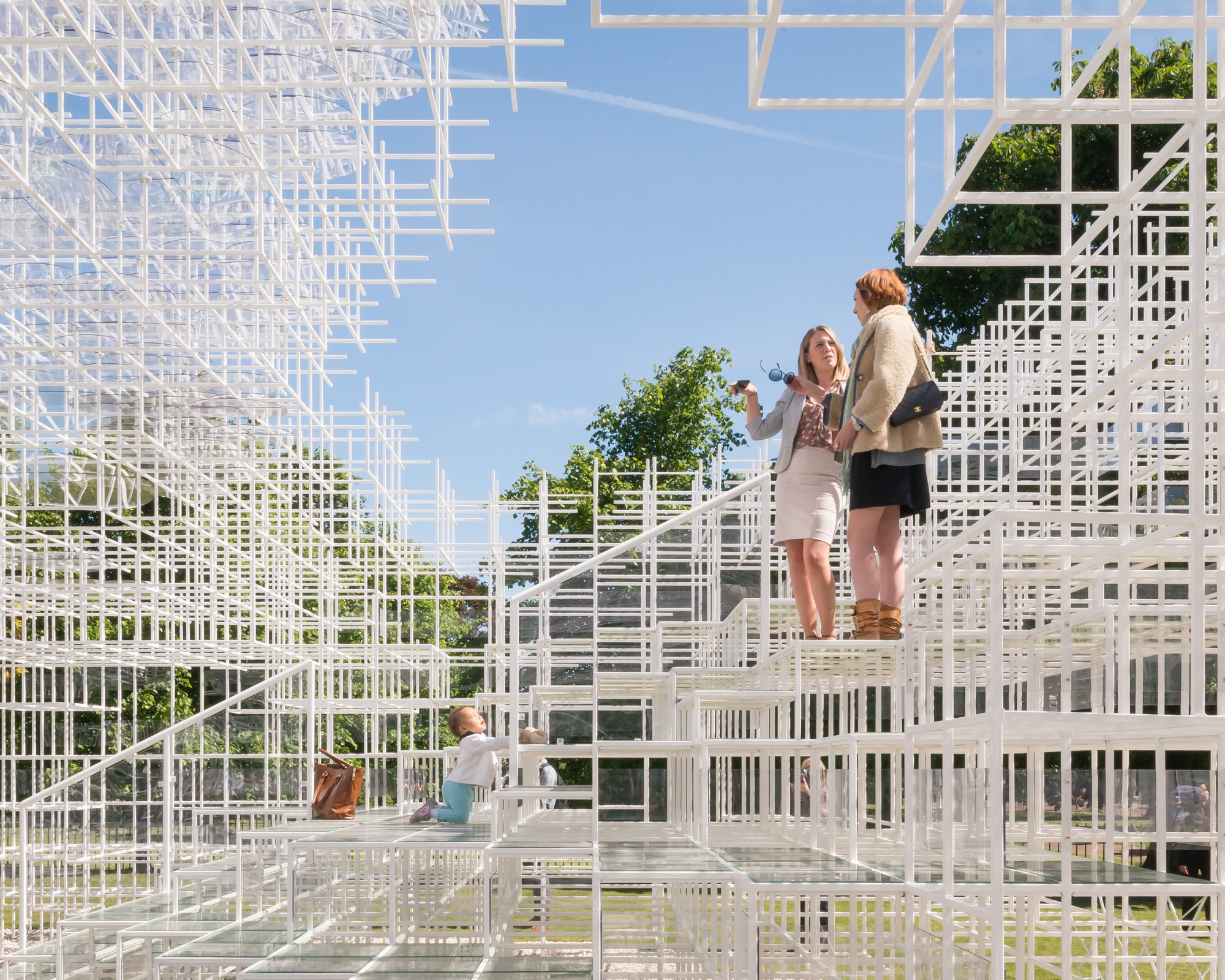

I refer to my work as “controlled chaos” and “managed mess.” Sometimes it’s a pair of shoes kicked off in the hall, and other times it’s a whole room that has been repurposed. In my experience, there have been times when architecture is used in unanticipated ways, and times when the design of a space allows for that transgression of use in a more purposeful and playful way. When I get to capture those moments, I know I’m going to have a good day.

In the era of the Instagram-ready project, there is a continuation of an age-old trend in architecture to create buildings as edifice. Looming large in our feeds, we are shown spaces that are clinically lined up, beautifully styled and dizzying in their scale and intention. Often there are no people present, and if there are, they are equally as manicured and posed as the bricks and mortar.

For many designers and architects, the idea that something which has been so carefully executed could be misused or misunderstood by the end user is a source of anxiety. Once the architect has left the building, though, there’s no recourse. I’ve seen it all: the good, the bad, and the ugly. And yet I find the larger concept of desire lines—the tracks left by people creating their own paths through green spaces—in architecture to be beautiful, a record of small acts of civil disobedience, resisting the CGI and well-considered plans. People showing they won’t be told what to do. These surprising and infinitely understandable acts of engagement certainly make for better images, filled with humor and humanity.

Much like a physical desire line in urban planning, a tension exists between what the architect intends and the eternal human yearning to have a choice, to not be dictated to, to resist or transgress.

In my opinion, the reason any of my images are successful is because they communicate the way the building in question is being used, and the more unexpected the better. I try to practice a slow, considered, experiential type of photography, and that means spending time in a place. The best, most successful (and fun) days are an act of collaboration between myself and the architect, and an often unspoken collaboration with the end users and the building itself.

With architect Tina Bergman in Sweden last year, I had originally planned to photograph a small cabin she designed when snow was on the ground, but due to rescheduling we ended up visiting the site in late September. Tina had driven us hours into the hills and the countryside, and we had happily chatted about life, work, bears, and driving in the dark.

The next morning, having arrived after sunset, we realized that we weren’t surrounded by snow, but instead, a glorious birch forest that had just turned all the shades of gold you could imagine. Electrified by the potential, I went to recce the site and ended up going on a long walk with Tina, the owner of the cabin, and her dog. When we returned to the cabin I got an opportunity to see what the structure was really made for. We left our shoes by the door, the fire was lit, we had coffee and cake, and I began the process of documentation in earnest unencumbered by any need to style and preen.

The resulting photographs are some of my favorites from that year, precisely because together, the three of us (and the dog) inhabited the space, showing how the little cabin, while having prescribed uses, also gives the people in that space an opportunity to choose how it gets used. The photographic series from that weekend tells a story of the place, and they show that Tina, as a designer, has listened not only to her client, but also the place in which the cabin is built. Her design allows the end user to impose a logic of their own on the space—something I have seen time and again in clever and generous design.

An end-of-terrace extension to a home in Glasgow might not be the most obvious gathering space for the local community, but Studio Kāp’s decision not to prescribe its use too specifically has created the dining room its client initially asked for: It is a prayer space, a room of counsel, an area for community meals, a homework desk, a dining room. Safe to say, the architects were thrilled about this outcome.

Years ago in Wrexham, whilst interviewing Sarah Featherstone of the architecture practice Featherstone Young for a film I was making about one of its projects—an art venue, market, and community space called Tŷ Pawb—she introduced me to its “baggy space” concept. Here was an idea, practical in its application, that explicitly said to the occupants of a building, “Here, it’s yours, you can do whatever you like with it.”

This has stuck with me. And I’m becoming increasingly convinced that the joy I find in the helium balloon clinging to the ceiling at Glasgow’s Kinning Park or at London’s Sands End Arts and Community Centre, or at the graffitied heart of Somerset’s East Quay—all mess, all signs of resistance to the styled and preened—are signs the building is loved. Signs that it does the job it’s supposed to for a person or group of people who feel comfortable enough there, who have been afforded enough agency, to make it their own.

An exhibition of Stephenson’s work, presented as a dual-screen film installation and titled “The Architect Has Left the Building,” is on view at Newcastle University’s Farrell Centre through February 25. It was previously on view at the Royal Institute of British Architects, which commissioned the project.

This story was written with Stephenson’s long-term creative partner and wife, Sofia-Kathryn Smith.