I recently counted the number of places I’ve lived in since I graduated from college, 20 years ago, and the number is 31. The list includes entries like “Park Slope random apartment I forgot about,” “tent,” “Eastern Parkway with ex-husband,” and “Eastern Parkway alone.” The last two are listed separately because they were wildly and incontrovertibly different places, even as they may have shared the same geographic location and the same four walls.

The longest I have lived in any one place since graduation is three years, in my first apartment (technically my second, but I lived in the first one for less than a week), in Berkeley, where I lived from 2010—when I started grad school—until I moved into an Oakland apartment with my soon-to-be-husband (and less-soon-to-be-ex-husband). I have owned and sold about 16 couches, eight desks, and innumerable chairs. I lose furniture the way other people lose umbrellas. When I got divorced, I gave away every single household object. When people ask me, aghast, how I can do this, I always say I’m just not object-oriented.

But that’s not the whole story. The truth is that I’m terrified to own anything, terrified to keep anything, and terrified to commit.

That Oakland apartment marked a pivotal point in my life. I was 28 when I moved into it with my college best friend, with whom I’d lived in “Portland NE Tillamook House,” and 31 when I moved out to live with my new boyfriend, with whom I would live in nine places. By this point, I had been writing professionally about architecture and design for eight years and had published hundreds of articles, many of which, in some way, argued for the importance of design, particularly for the way in which residential design impacted our lives.

My book, Dark Nostalgia, had come out a year before and in it I had explored, among other ideas, the threshold condition between public life and private life, and argued for the ways in which drapery, furniture, and the well-placed rug shifted and indicated to the resident and visitor what kind of a day should be lived. In all of my writing, I was devoted to a singular pursuit: making people care about architecture and design. And yet, deep into a career as a design critic and thinker, I had yet to ever settle in. I had yet to ever feel at home.

For the year I’d lived in “Portland NE Tillamook House” with that best friend, I’d had a mattress on the floor. That was it. No dresser, no nightstand, no lamp. At night, I put myself to sleep by reading a book (we didn’t have iPhones yet) by the light of the one single glaring overhead light, which I had to get out of bed (my floor mattress) to turn off.

I lived that way—while writing evocative articles about home and design, and applying to graduate school with the proposal to study the concept of home—until my mother came to visit and, horrified by what had become of her only daughter, bought me a dresser, a nightstand, and a lamp.

My friend had witnessed all this, and, as we signed the Oakland lease and faced the roommate bedroom choice, knew that if someone—in this case, he—didn’t intervene, I’d do the same thing again. In a profound act of friendship, he made me an offer: I could take the bigger of the two bedrooms, but only if I furnished it. I accepted immediately, not quite understanding what I was signing up for, and how difficult it would be.

A day later we were in an Emeryville IKEA, and I was crying. I was standing in the home office section, trying to pick a desk. Did I want a curved wooden desk, or a straight metal one? Did I want one with storage, or without? My friend passed me by, his cart full of things he instinctively knew he wanted. “I can’t decide,” I told him. “I really can’t.” I just had to pick something, he said. We needed to leave in 20 minutes.

So I picked the blankest desk I could find, a plain white LINNMON/ADILS, the desk with the fewest features. After that, we went to a vintage furniture store in downtown Oakland and I got a dresser for $200. Slowly, I added a poster. A chair. And yet.

The divide between what I was saying and what I was living was only getting bigger. I was just starting a graduate degree, for which I had professed my intention to spend six to eight years studying the concept of home from an architectural perspective. As I read book after book about the emotions of home and the construction of place, and as I developed a thesis about love and intimacy, I would spend the next eight years living in 12 other places. Even now, I’m writing this from an apartment in Los Angeles while waiting to see if we got the other place we just applied for. I hope we can break our lease. And we’ll definitely need a new couch.

I know some therapists. One of them, my friend Hannah, sent me a few thoughts after I asked her to theorize about what might be going on. “Even if we on some level dislike the idea of impermanence, we tend to, at least subconsciously, lean on what is familiar,” she says. “You can say, ‘I hated moving around growing up,’ and mean it, but still feel the most comfortable with it. It’s the devil we know, and that’s psychologically safer than something we don’t know—even if it’s more promising.”

This sounds right to me. I grew up across cities and countries, attended 12 schools by the time I started college, and felt like I was always starting over, like I should always actually be somewhere else.

But what, I ask Hannah, about this feeling that I’m an imposter in my field, and that this is the biggest lie of all? “The choice to make it your career is a way to engage with the ambivalence without fully committing to a foreign life,” she says. “It’s a foot in. It could even serve as a way to be a voyeur into a life that is unknown.”

What about architects? Do they deal with this ambivalence via their clients? A friend of mine, Robin Donaldson, just built a house for a couple who know that they will never leave it, who have committed to every curve of concrete, every expanse of glass. The house is extraordinary, of course, and it seems to me a commitment beyond marriage—even beyond having a child, in some ways.

I wonder if it was easy for them, or for Robin’s other clients, most of whom, following his vision, build large and unusual homes. “This is where my psychiatry fee comes in,” he jokes at first. But then: “It’s a very common issue.” He says people start thinking about a project as their forever home; some might even realize they’re thinking about where (if all goes well) they’ll die. And that’s when they—like me, at the IKEA—get freaked about every decision. Every breakfast nook feels like the only breakfast nook. Every chair feels like an eternity.

So how does he deal? “I focus on the pragmatics of the project,” he says. “I have to take people out of the dark corner that they work themselves into, and take it back to a more pragmatic place.” Instead of highlighting that this is the bedroom is where it might go down, no take-backs, Donaldson highlights that this is the situationally best place for the kitchen, the objectively ideal moment for the sun.

It usually works. Or maybe, I think, it’s just easier for rich people to commit without panicking because they actually can make sure they have everything they need materially, that they’ve covered all the bases.

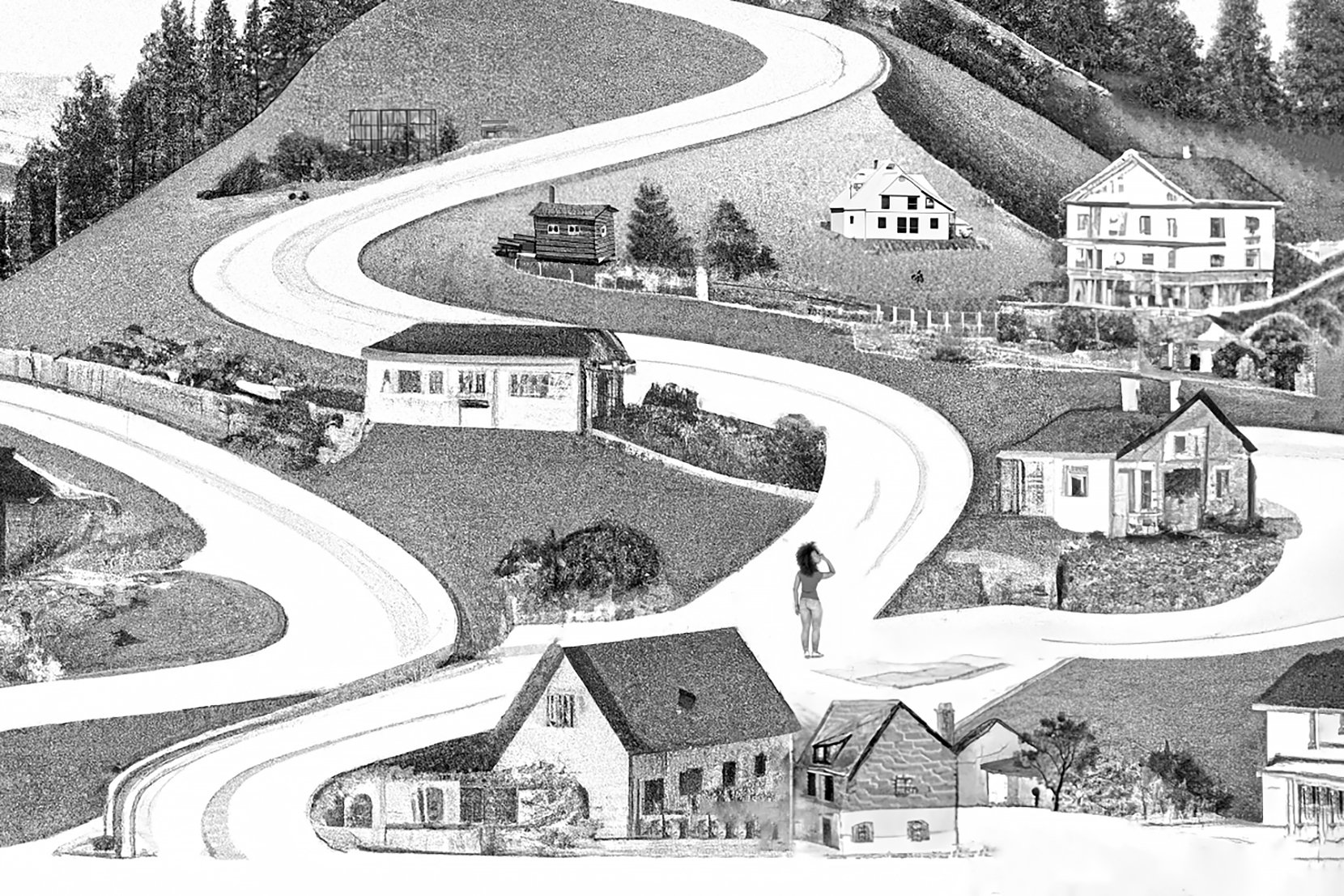

Maybe part of my fear is that I’ll miss out. That I’ll make the wrong choice, with disastrous and unfixable consequences that I could only have prevented with a different standing desk. But, as we all know, some of the richest people are also some of the most miserable. And maybe without an architect guiding them, they’d be like me: standing in a field, wondering where their living room should go, paralyzed with indecision. It’s not that they’ve solved the problem any more than I have. They’ve just outsourced it.

In some ways, lucky for me, architectural historians are newly interested in the history of emotions. “It’s a foot in,” as my friend Hannah said. One of my graduate school professors, Greg Castillo, has done work in this world, but I don’t want to call him: He was involved in my most emotional graduate school situation.

But thinking about tracking him down leads me to Sara Honarmand Ebrahimi, who writes that the key to understanding the relationship between architecture and emotions is to begin with acknowledging that “emotions themselves have a history as complex as the history of the buildings in which they are felt and expressed.” And maybe that’s where I should start: by thinking less about the buildings, and more about the emotional history. And so.

I have been trained as a historian to look through the evidence and to follow the archive. And the evidence here is clear: This is not a series of accidents of life, not a pattern of unfortunate and unavoidable events that have led me to this world of material instability and chaotic residency, of tenuous connection to home. It’s not constant circumstances beyond my control, as I have always believed it is, or something that will change tomorrow, once I end up somewhere different, once I really find the right house. In the words of Taylor Swift: “Hi, it’s me. I’m the problem.” And until I want to change, I won’t.

I really hope I get that apartment. It might really be the one.