ISSUE↓

STORY TYPE↓

AUTHOR↓

14

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

April 28, 2025

Neuroaesthetics Has Been Around for 25 Years. Are Architects Paying Attention Yet?

by Diana Budds

14

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

April 14, 2025

How Food Forests Could Reshape Our Cities

by LinYee Yuan

14

OBJECTS AND THINGS

April 21, 2025

Furniture That Supports Us, When and Where We Need It

by Anjulie Rao

14

OBJECTS AND THINGS

April 7, 2025

Peter Shire and Ryan Preciado Talk Cups, Memphis, and Making Things That Last

by Jonathan Griffin

14

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

March 24, 2025

What Terra-Cotta Can Teach Us About Beauty

by Kriston Capps

14

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

March 10, 2025

Handling Hardware: Modernism and the Door

by Edwin Heathcote

14

PERSPECTIVE

February 24, 2025

Why Are Most Real Estate Listings a Vibe Killer?

by FOR SCALE

14

PERSPECTIVE

February 17, 2025

Hey, City Planners: Pay Attention to Skateboarders

by Zach Moldof

14

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

February 10, 2025

The Overlooked Intelligence of Architectural B-Sides

by Charlie Weak

14

BOOK REVIEW

February 3, 2025

After a 50-Year Pause, Archigram Keeps the Dream Alive

by Anthony Paletta

14

PEOPLE

January 21, 2025

In Praise of the Pedestrian

by Phillip Cox

13

PERSPECTIVE

December 16, 2024

Some Chests of Drawers I Have Known

by Roy McMakin

13

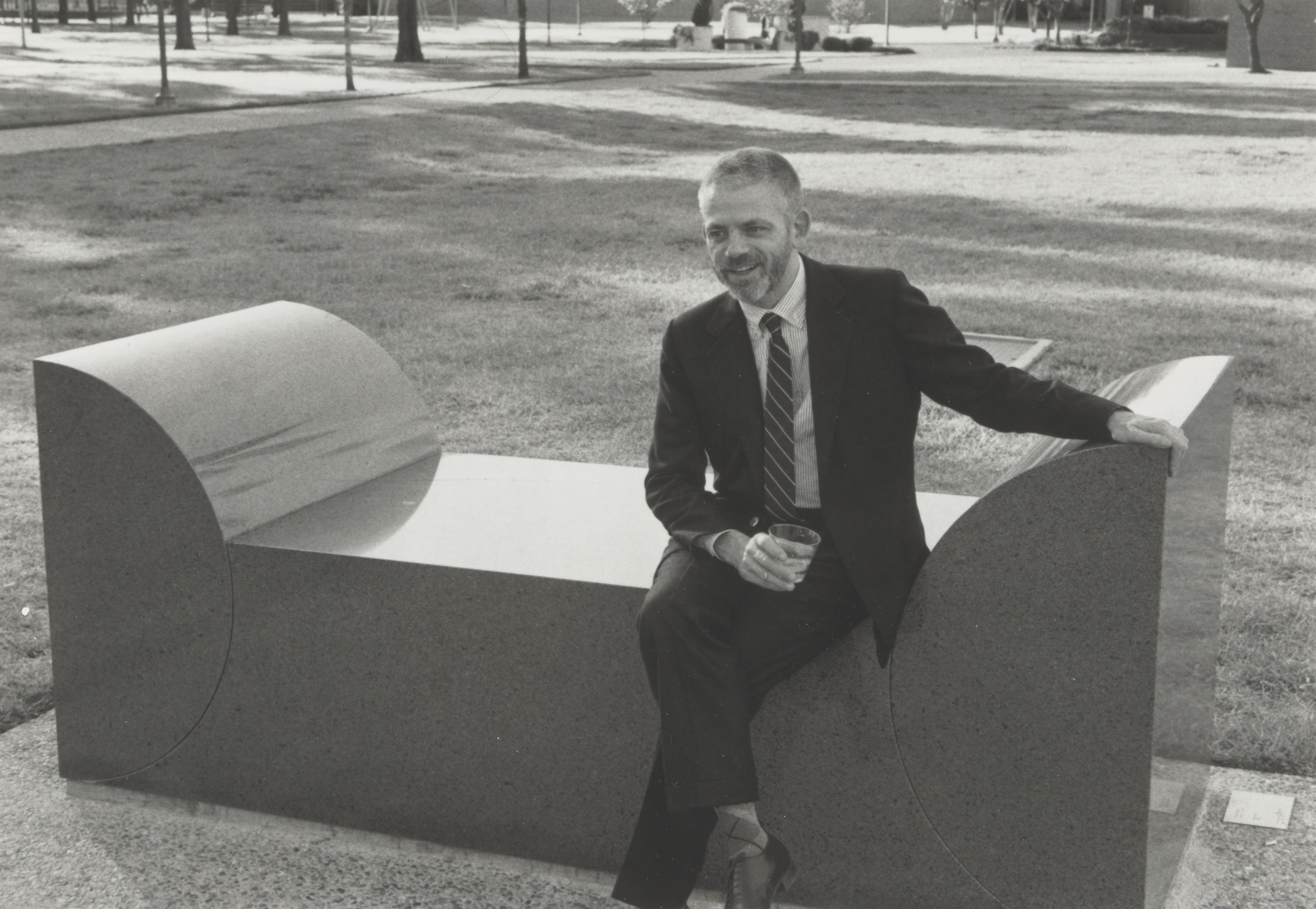

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

December 9, 2024

Why Are Scott Burton’s Benches Disappearing?

by Mark Byrnes

13

BOOK REVIEW

November 25, 2024

A Mind-Body Experience of Architecture, Delivered in a Photo

by Marianela D’Aprile

13

PERSPECTIVE

November 18, 2024

Seeing Chinatown as a Readymade

by Philip Poon

13

PEOPLE

November 11, 2024

The Place of the Handmade Artifact in a Tech-Obsessed Era

by Anne Quito

13

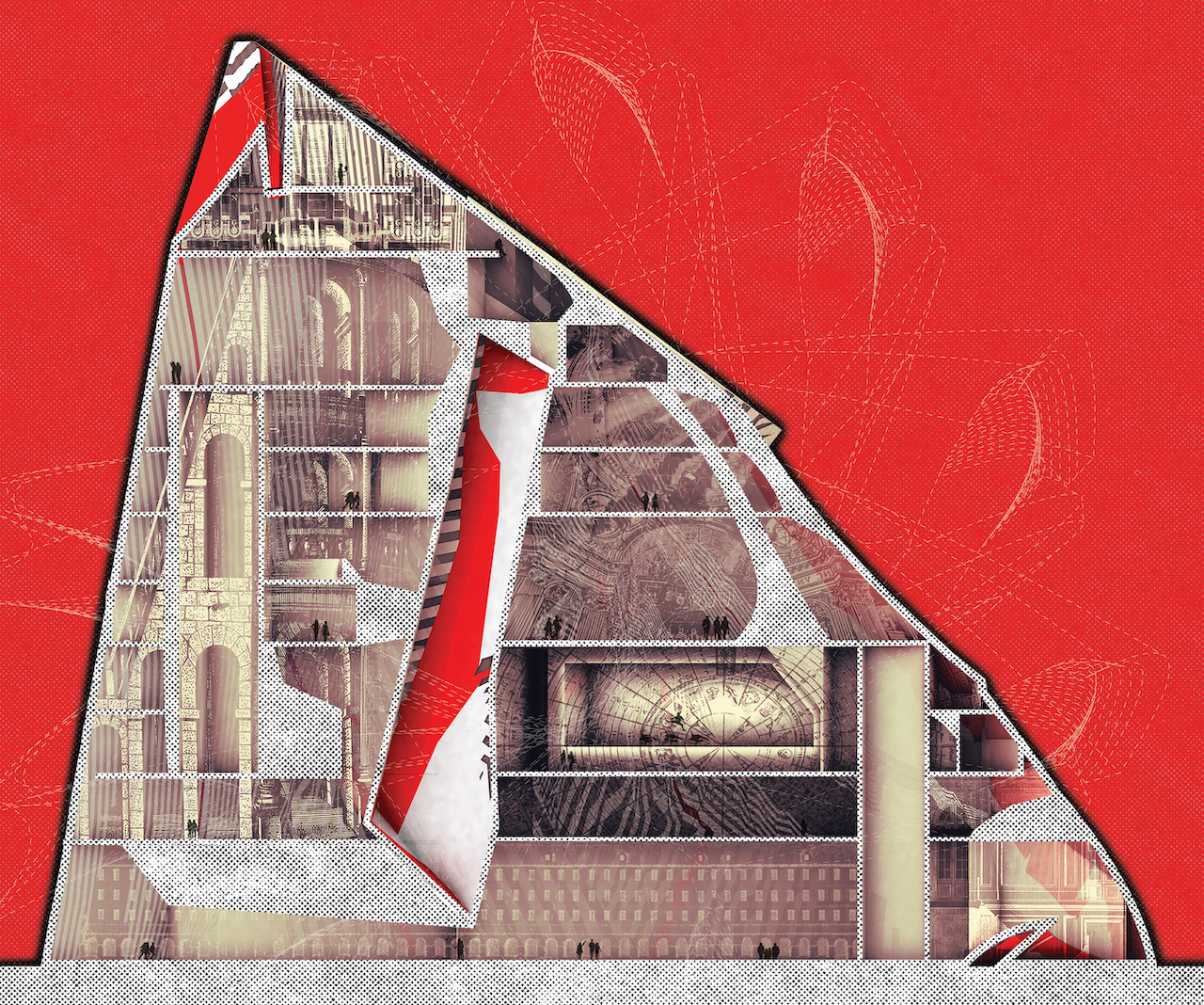

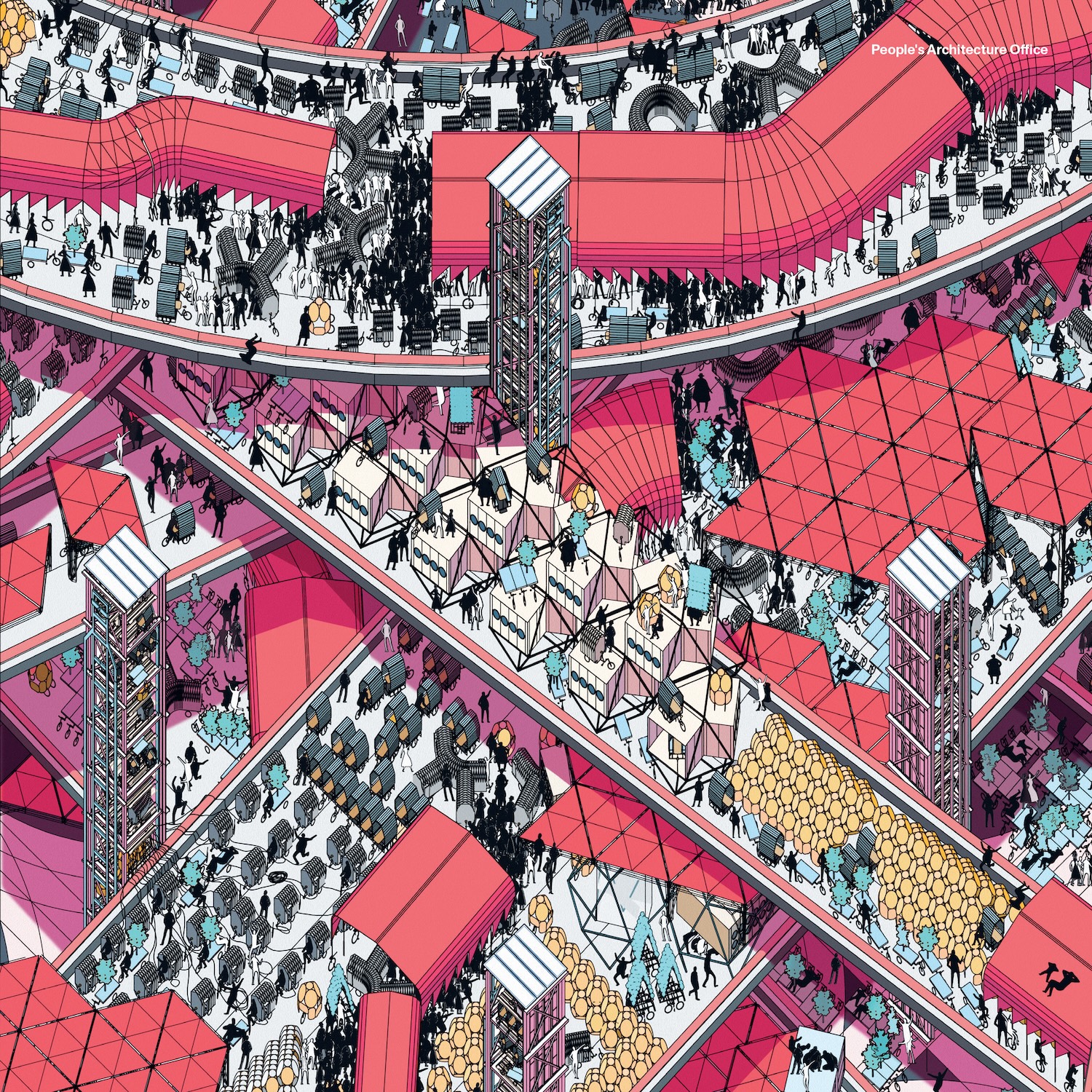

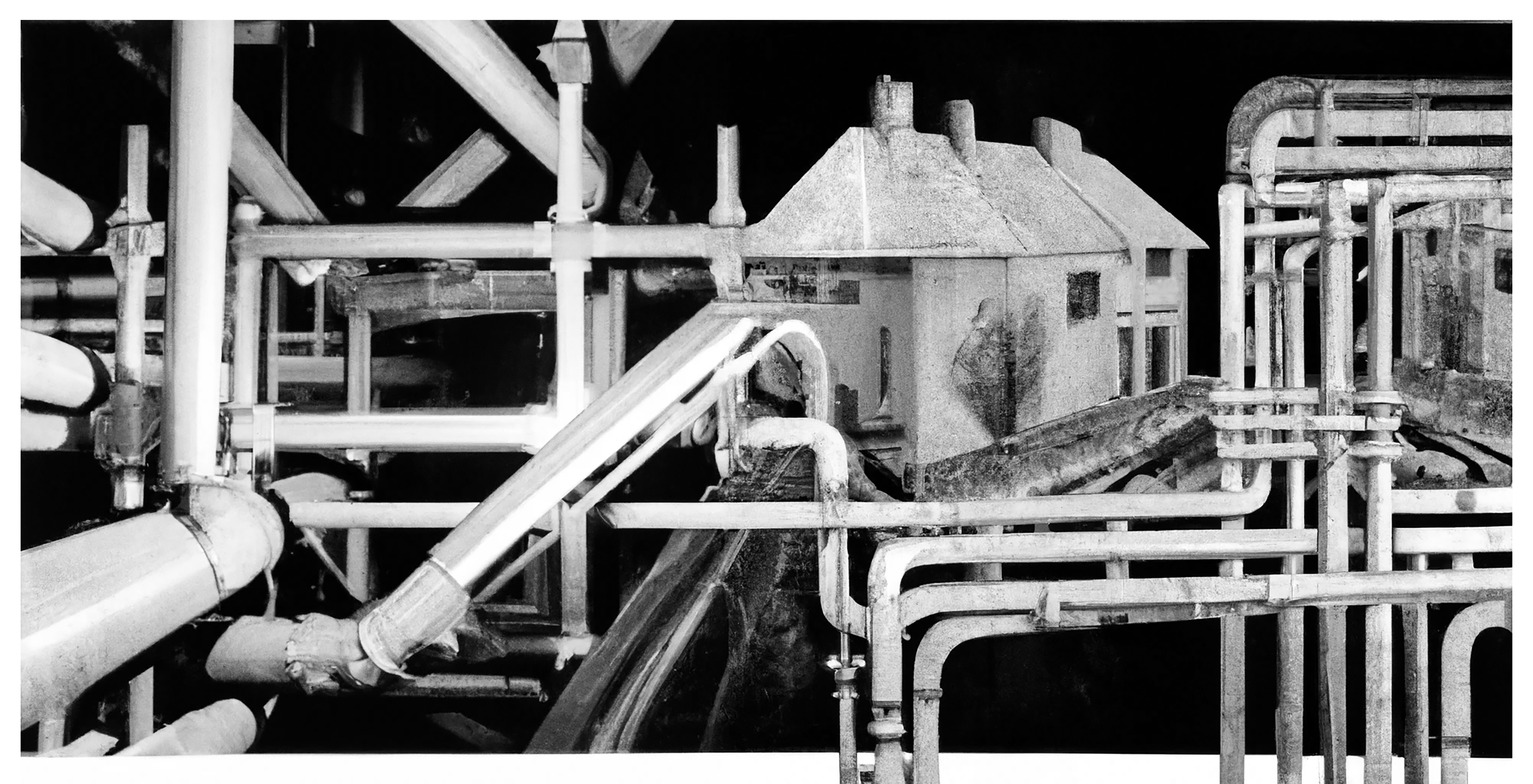

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

November 4, 2024

How a Storied Printmaker Advances the Practice of Architecture

by Diana Budds

12

PEOPLE

October 21, 2024

Sounding Out a Better Way to Build

by Jesse Dorris

12

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

October 7, 2024

What It Means—and What It’s Worth—to Be “Light”

by Julie Lasky

12

PERSPECTIVE

September 23, 2024

Redefining “Iconic” Architecture and Ideals

by Sophie Lovell

12

PERSPECTIVE

September 9, 2024

Surrendering to What Is

by Marianne Krogh

11

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

August 26, 2024

Sometimes, Democratic Design Doesn’t “Look” Like Anything

by Zach Mortice

11

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

August 19, 2024

What Does Your Home Say About You?

by Shane Reiner-Roth

11

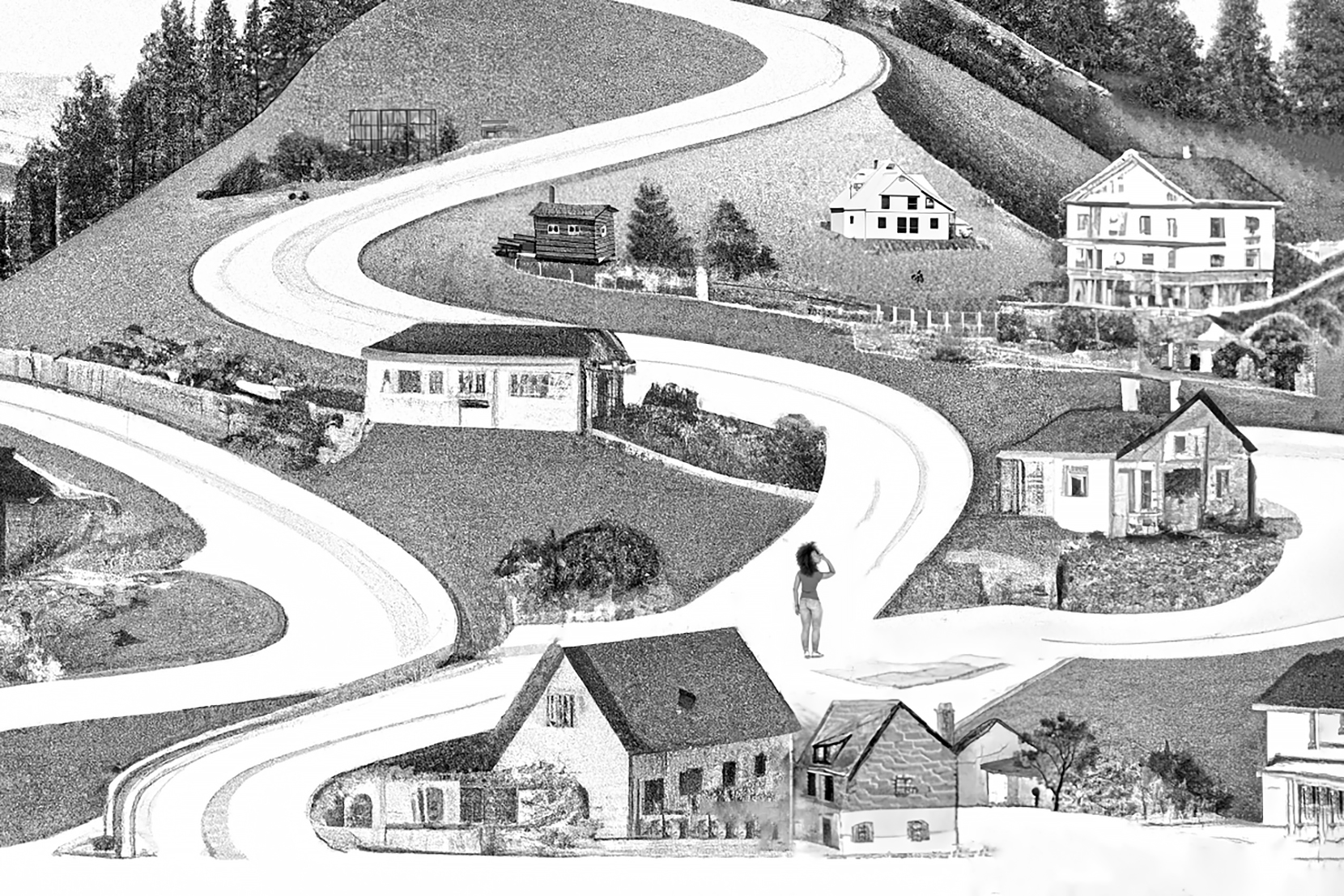

BOOK REVIEW

August 12, 2024

Is Building Better Cities a Dream Within Reach?

by Michael Webb

11

PEOPLE

August 5, 2024

The Value of Unbuilt Buildings

by George Kafka

11

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

July 29, 2024

Future-Proofing a Home Where Water Is a Focus and a Thread

by Alexandra Lange

11

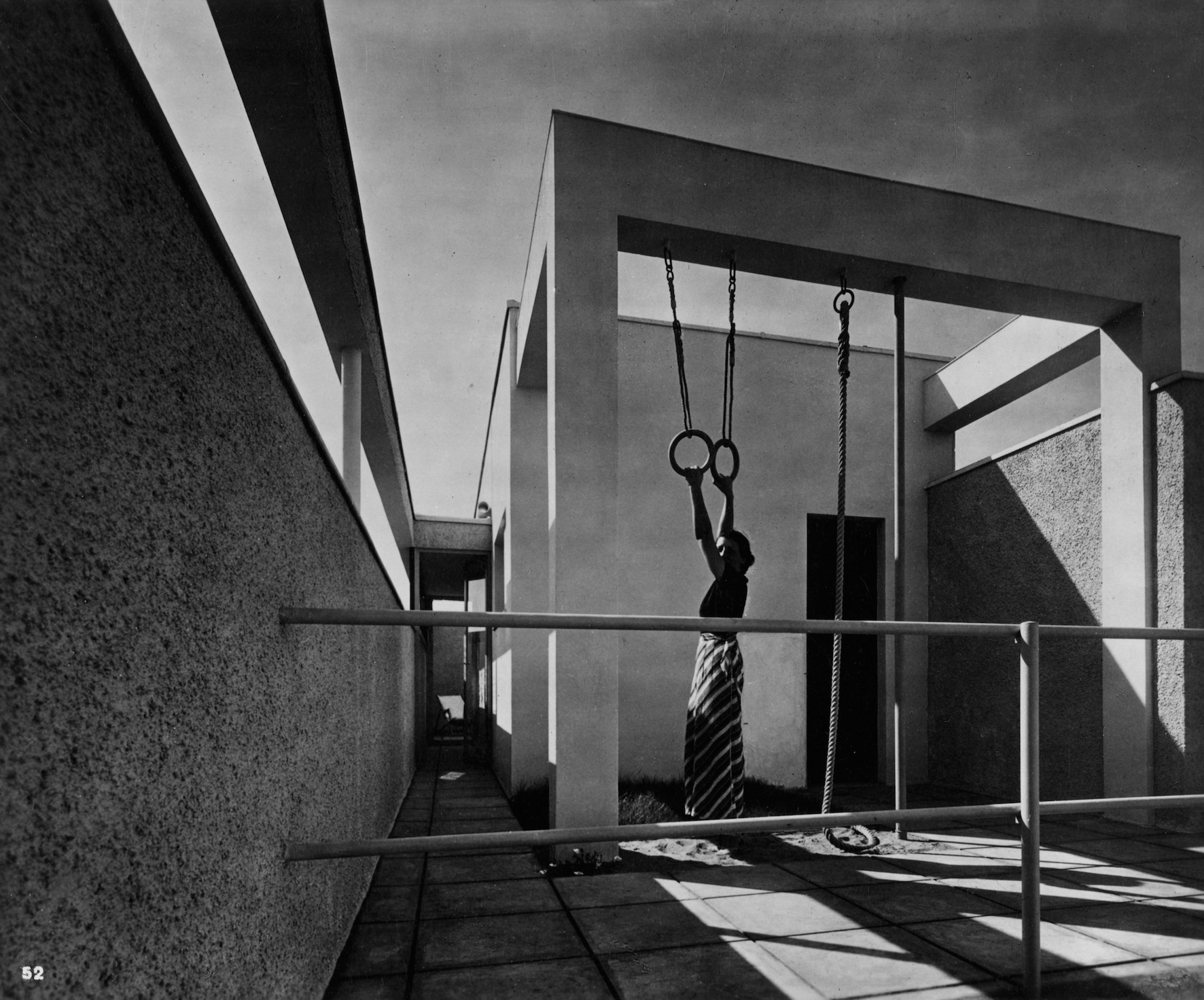

BOOK REVIEW

July 22, 2024

Modernist Town, U.S.A.

by Ian Volner

11

PEOPLE

July 15, 2024

Buildings That Grow from a Place

by Anthony Paletta

10

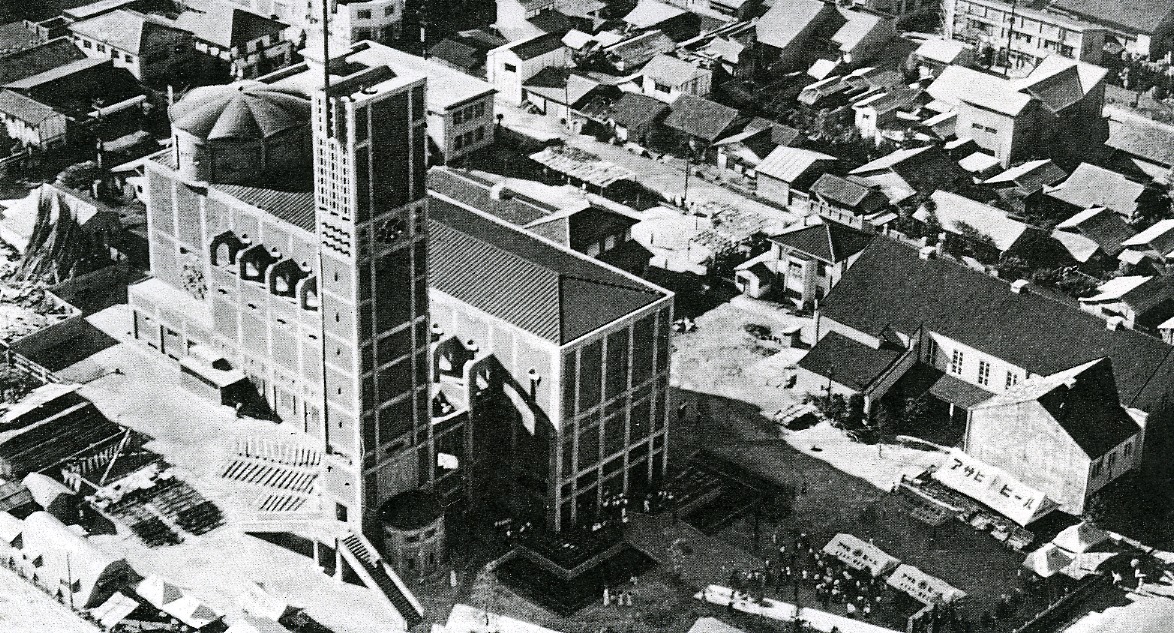

URBANISM

June 24, 2024

What We Lose When a Historic Building Is Demolished

by Owen Hatherley

10

PERSPECTIVE

June 17, 2024

We Need More Than Fewer, Better Things

by Deb Chachra

10

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

June 3, 2024

An Ode to Garages

by Charlie Weak

10

PERSPECTIVE

May 28, 2024

In Search of Domestic Kintsugi

by Edwin Heathcote

10

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

May 13, 2024

The Perils of the Landscapes We Make

by Karrie Jacobs

10

PERSPECTIVE

May 6, 2024

Using Simple Tools as a Radical Act of Independence

by Jarrett Fuller

9

PERSPECTIVE

April 29, 2024

Why Can’t I Just Go Home?

by Eva Hagberg

9

PEOPLE

April 22, 2024

Why Did Our Homes Stop Evolving?

by George Kafka

9

ROUNDTABLE

April 8, 2024

Spaces Where the Body Is a Vital Force

by Tiffany Jow

9

BOOK REVIEW

April 1, 2024

Tracing the Agency of Women as Users and Experts of Architecture

by Mimi Zeiger

9

PERSPECTIVE

March 25, 2024

Are You Sitting in a Non-Place?

by Mzwakhe Ndlovu

9

ROUNDTABLE

March 11, 2024

At Home, Connecting in Place

by Marianela D’Aprile

9

PEOPLE

March 4, 2024

VALIE EXPORT’s Tactical Urbanism

by Alissa Walker

8

PERSPECTIVE

February 26, 2024

What the “Whole Earth Catalog” Taught Me About Building Utopias

by Anjulie Rao

8

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

February 19, 2024

How a Run-Down District in London Became a Model for Neighborhood Revitalization

by Ellen Peirson

8

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

February 12, 2024

In Brooklyn, Housing That Defies the Status Quo

by Gideon Fink Shapiro

8

PERSPECTIVE

February 5, 2024

That “Net-Zero” Home Is Probably Living a Lie

by Fred A. Bernstein

8

PERSPECTIVE

January 22, 2024

The Virtue of Corporate Architecture Firms

by Kate Wagner

8

PERSPECTIVE

January 16, 2024

How Infrastructure Shapes Us

by Deb Chachra

8

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

January 8, 2024

The Defiance of Desire Lines

by Jim Stephenson

7

PEOPLE

December 18, 2023

This House Is Related to You and to Your Nonhuman Relatives

by Sebastián López Cardozo

7

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

December 11, 2023

What’s the Point of the Plus Pool?

by Ian Volner

7

BOOK REVIEW

December 4, 2023

The Extraordinary Link Between Aerobics and Architecture

by Jarrett Fuller

7

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

November 27, 2023

Architecture That Promotes Healing and Fortifies Us for Action

by Kathryn O’Rourke

7

PEOPLE

November 6, 2023

How to Design for Experience

by Diana Budds

7

PEOPLE

October 30, 2023

The Meaty Objects at Marta

by Jonathan Griffin

6

OBJECTS

October 23, 2023

How Oliver Grabes Led Braun Back to Its Roots

by Marianela D’Aprile

6

URBANISM

October 16, 2023

Can Adaptive Reuse Fuel Equitable Revitalization?

by Clayton Page Aldern

6

PERSPECTIVE

October 9, 2023

What’s the Point of a Tiny Home?

by Mimi Zeiger

6

OBJECTS

October 2, 2023

A Book Where Torn-Paper Blobs Convey Big Ideas

by Julie Lasky

6

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

September 24, 2023

The Architecture of Doing Nothing

by Edwin Heathcote

6

BOOK REVIEW

September 18, 2023

What the “Liebes Look” Says About Dorothy Liebes

by Debika Ray

6

PEOPLE

September 11, 2023

Roy McMakin’s Overpowering Simplicity

by Eva Hagberg

6

OBJECTS

September 5, 2023

Minimalism’s Specific Objecthood, Interpreted by Designers of Today

by Glenn Adamson

5

ROUNDTABLE

August 28, 2023

How Joan Jonas and Eiko Otake Navigate Transition

by Siobhan Burke

5

OBJECTS

August 21, 2023

The Future-Proofing Work of Design-Brand Archivists

by Adrian Madlener

5

URBANISM

August 14, 2023

Can a Church Solve Canada’s Housing Crisis?

by Alex Bozikovic

5

PEOPLE

August 7, 2023

In Search of Healing, Helen Cammock Confronts the Past

by Jesse Dorris

5

URBANISM

July 31, 2023

What Dead Malls, Office Parks, and Big-Box Stores Can Do for Housing

by Ian Volner

5

PERSPECTIVE

July 24, 2023

A Righteous Way to Solve “Wicked” Problems

by Susan Yelavich

5

OBJECTS

July 17, 2023

Making a Mess, with a Higher Purpose

by Andrew Russeth

5

ROUNDTABLE

July 10, 2023

How to Emerge from a Starchitect’s Shadow

by Cynthia Rosenfeld

4

PEOPLE

June 26, 2023

There Is No One-Size-Fits-All in Architecture

by Marianela D’Aprile

4

PEOPLE

June 19, 2023

How Time Shapes Amin Taha’s Unconventionally Handsome Buildings

by George Kafka

4

PEOPLE

June 12, 2023

Seeing and Being Seen in JEB’s Radical Archive of Lesbian Photography

by Svetlana Kitto

4

PERSPECTIVE

June 5, 2023

In Built Environments, Planting Where It Matters Most

by Karrie Jacobs

3

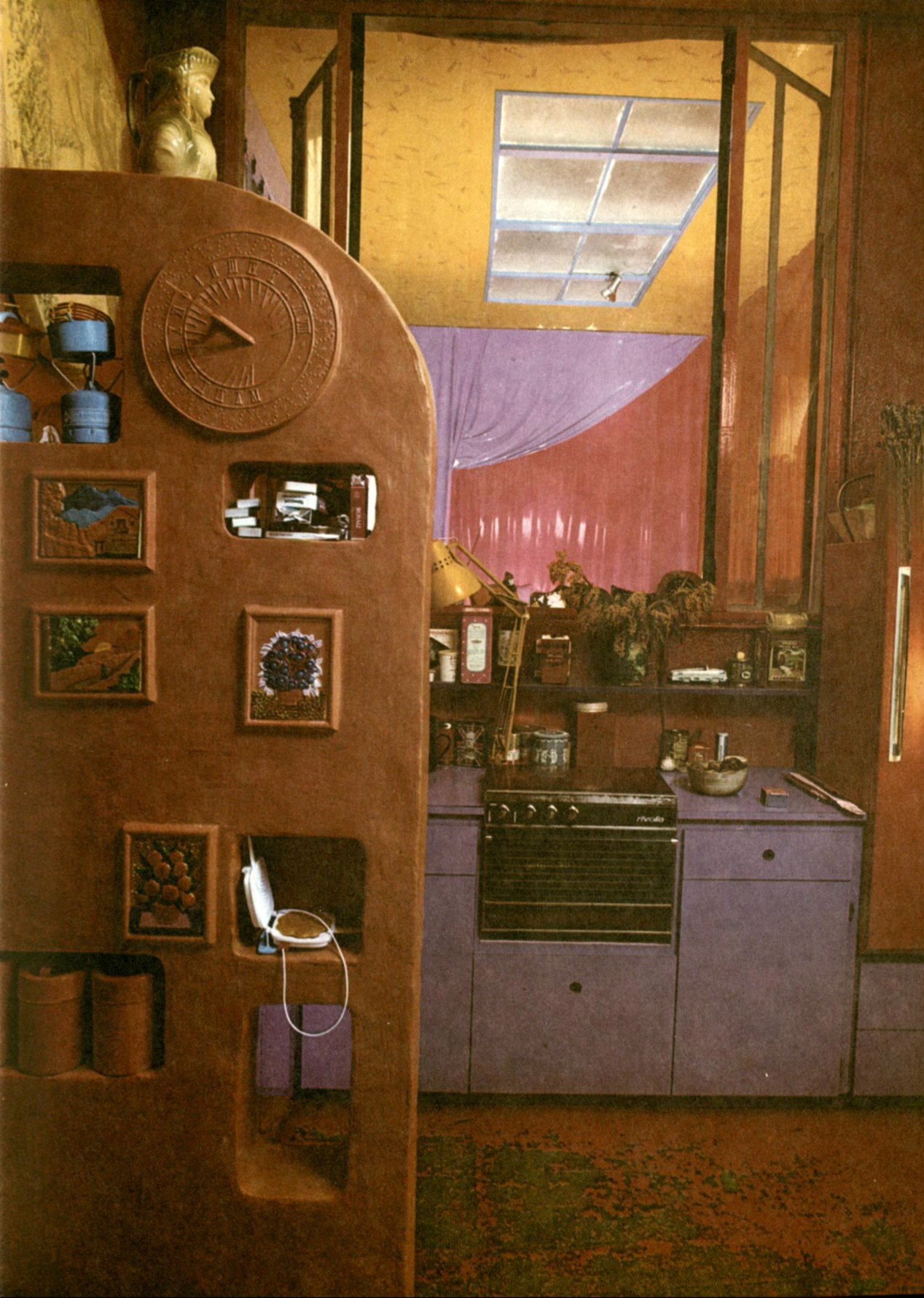

PERSPECTIVE

May 30, 2023

On the Home Front, a Latine Aesthetic’s Ordinary Exuberance

by Anjulie Rao

3

PERSPECTIVE

May 21, 2023

For a Selfie (and Enlightenment), Make a Pilgrimage to Bridge No. 3

by Alexandra Lange

3

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

May 8, 2023

The Building Materials of the Future Might Be Growing in Your Backyard

by Marianna Janowicz

3

BOOK REVIEW

May 1, 2023

Moving Beyond the “Fetishisation of the Forest”

by Edwin Heathcote

2

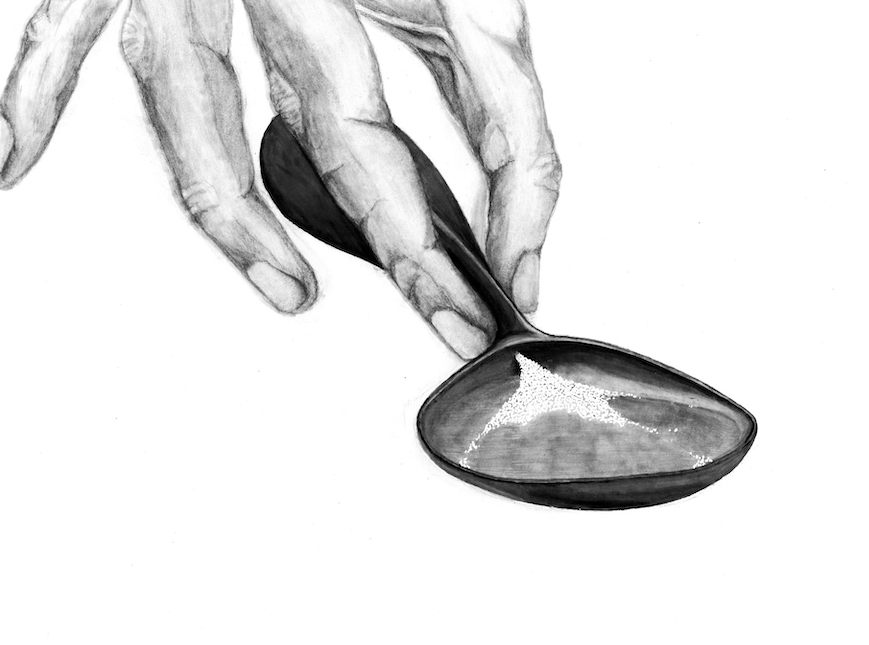

ROUNDTABLE

April 24, 2023

Is Craft Still Synonymous with the Hand?

by Tiffany Jow

2

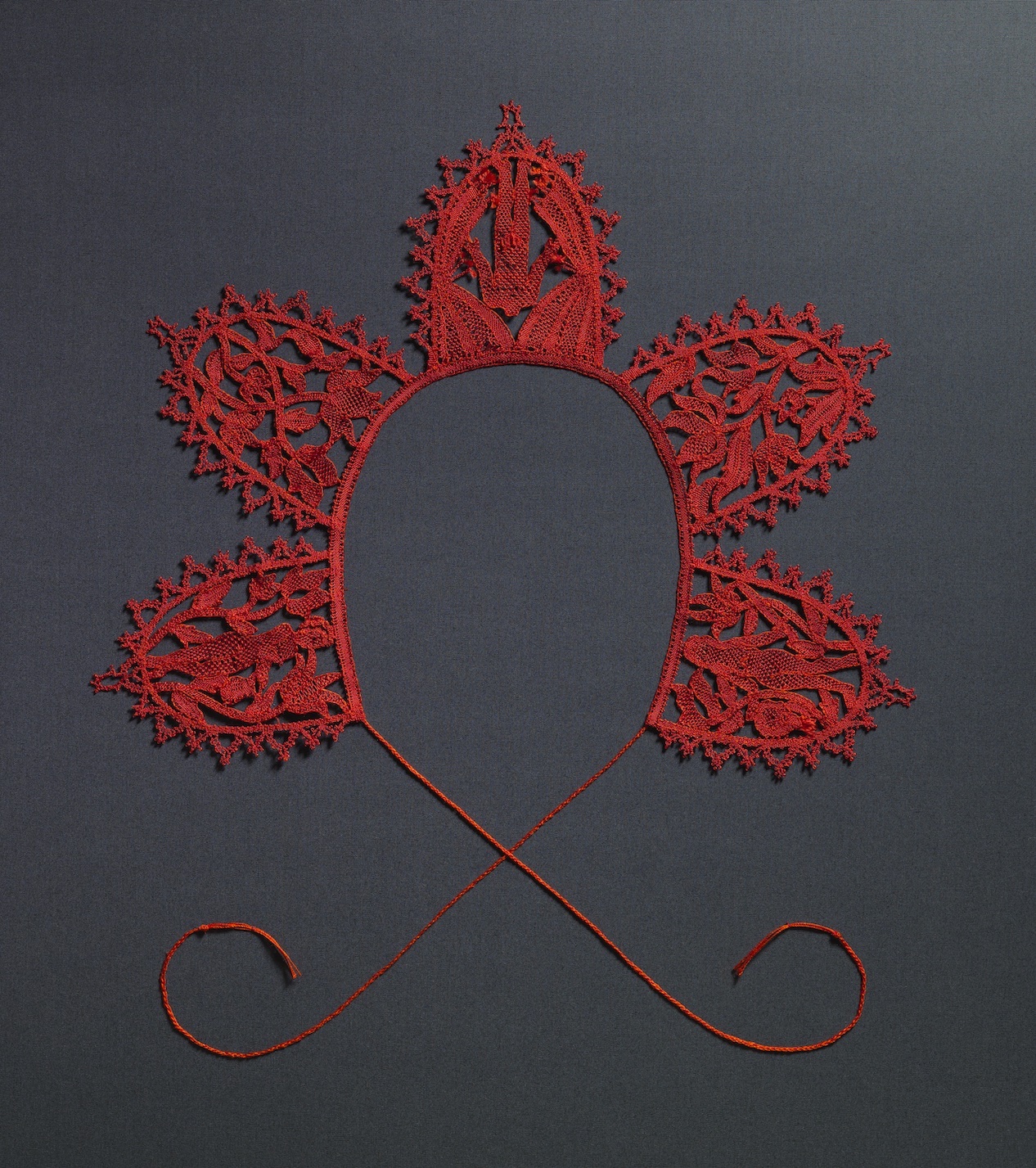

PEOPLE

April 17, 2023

A Historian Debunks Myths About Lacemaking, On LaceTok and IRL

by Julie Lasky

2

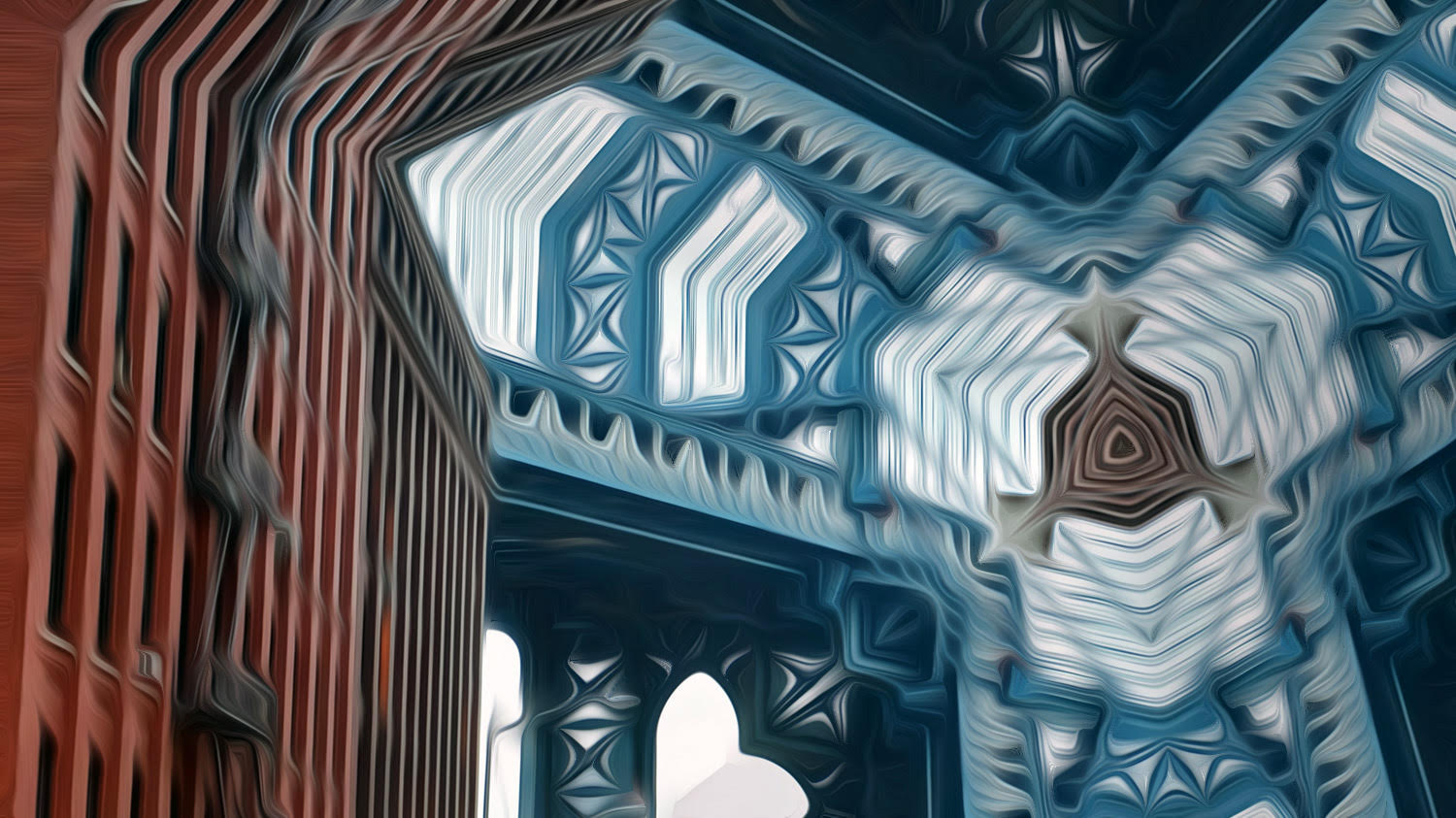

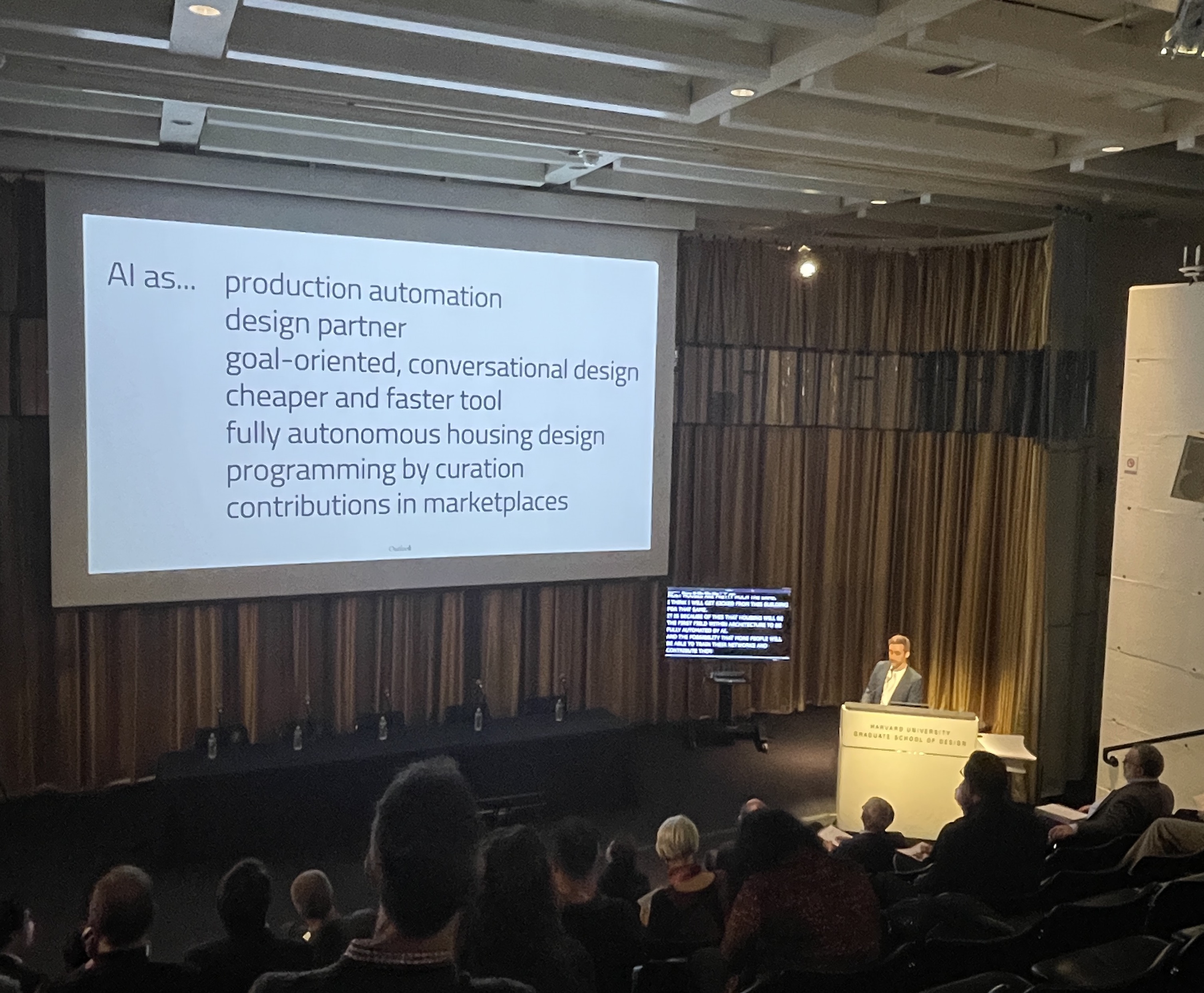

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

April 10, 2023

How AI Helps Architects Design, and Refine, Their Buildings

by Ian Volner

2

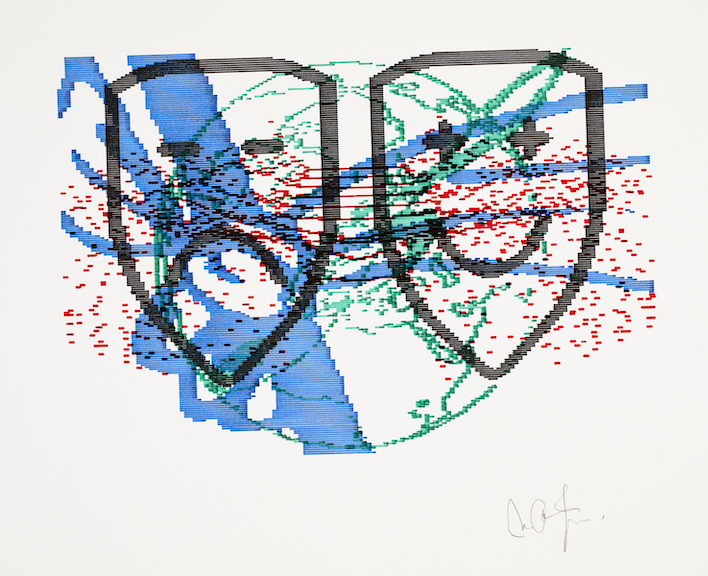

PEOPLE

April 3, 2023

Merging Computer and Loom, a Septuagenarian Artist Weaves Her View of the World

by Francesca Perry

1

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

March 27, 2023

Words That Impede Architecture, According to Reinier de Graaf

by Osman Can Yerebakan

1

PEOPLE

March 20, 2023

Painting With Plaster, Monica Curiel Finds a Release

by Andrew Russeth

1

PERSPECTIVE

March 13, 2023

Rules and Roles in Life, Love, and Architecture

by Eva Hagberg

1

Roundtable

March 6, 2023

A Design Movement That Pushes Beyond Architecture’s Limitations

by Tiffany Jow

0

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

February 7, 2023

To Improve the Future of Public Housing, This Architecture Firm Looks to the Past

by Ian Volner

0

OBJECTS

February 7, 2023

The Radical Potential of “Prime Objects”

by Glenn Adamson

0

PEOPLE

February 20, 2023

Xiyadie’s Queer Cosmos

by Xin Wang

0

PEOPLE

February 13, 2023

How Michael J. Love’s Subversive Tap Dancing Steps Forward

by Jesse Dorris

0

SHOW AND TELL

February 7, 2023

Finding Healing and Transformation Through Good Black Art

by Folasade Ologundudu

0

BOOK REVIEW

February 13, 2023

How Stephen Burks “Future-Proofs” Craft

by Francesca Perry

0

ROUNDTABLE

February 27, 2023

Making Use of End Users’ Indispensable Wisdom

by Tiffany Jow

0

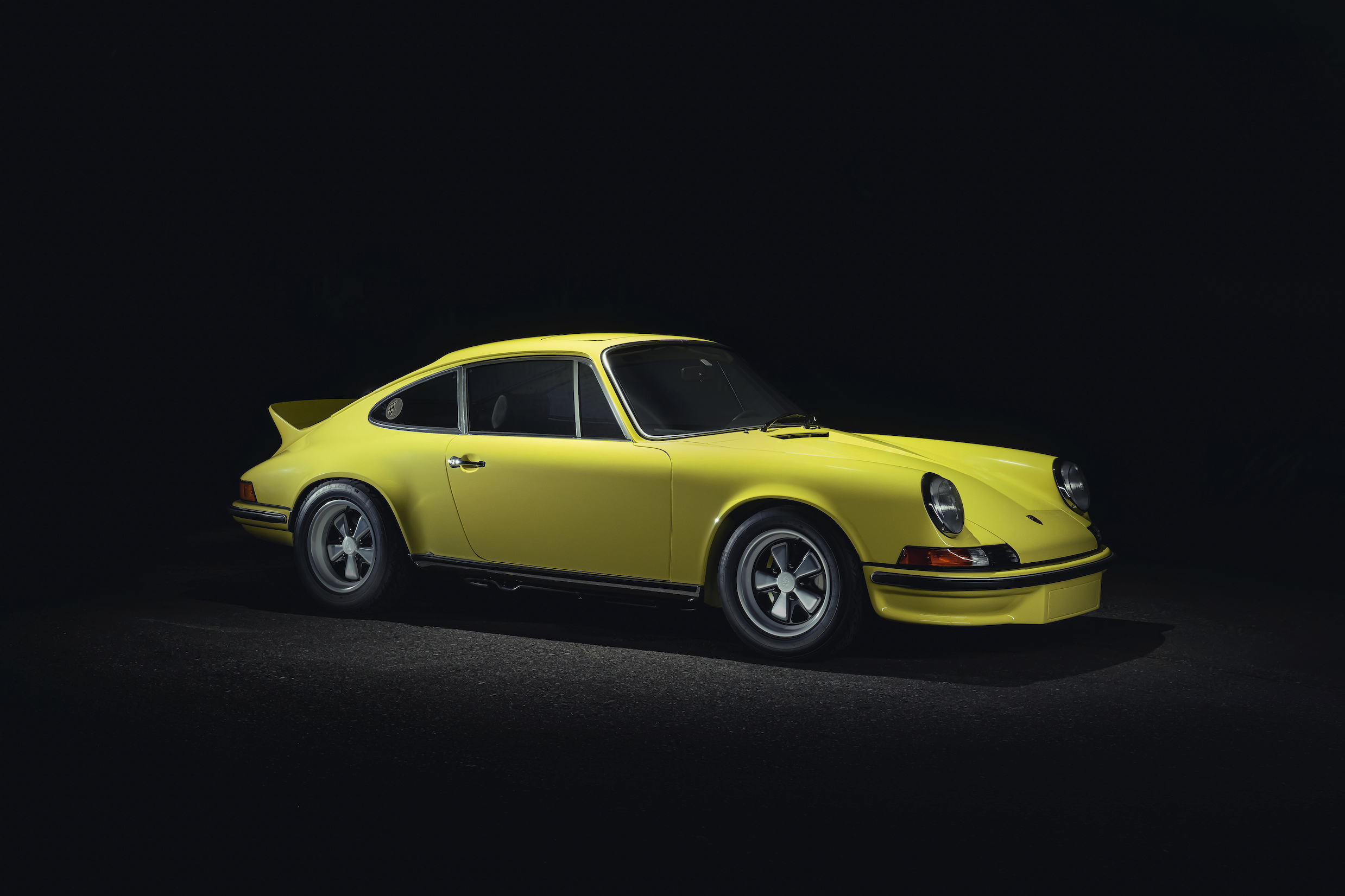

PEOPLE

February 7, 2023

The New Lessons Architect Steven Harris Learns from Driving Old Porsches

by Jonathan Schultz

0

PERSPECTIVE

February 7, 2023

The Day Architecture Stopped

by Kate Wagner

0

OBJECTS

February 7, 2023

The Overlooked Potential of Everyday Objects

by Adrian Madlener

0

ROUNDTABLE

February 7, 2023

A Conversation About Generalists, Velocity, and the Source of Innovation

by Tiffany Jow

0

OBJECTS

February 7, 2023

Using a Fungi-Infused Paste, Blast Studio Turns Trash Into Treasure

by Natalia Rachlin